|

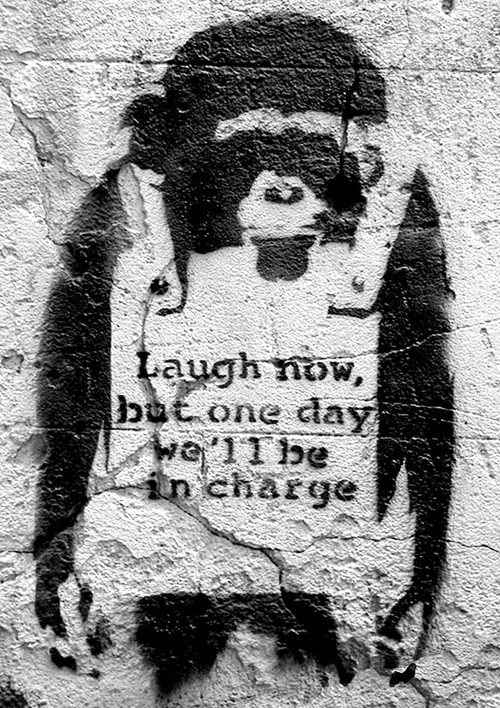

It is possible to view the history of art as a house with many levels. Fancifully, if we were to take a tour we might discover the prehistoric cave paintings at Altamira and Lascaux in the cellar before ascending to windowed rooms where we’ll find Egyptian art. Another staircase will take us to floors crammed with works from the Renaissance. As we climb further up the building we’ll pass through floors containing Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical art. The 19th century alone will contain numerous floors. By the time we reach the 20th century we’ll be many, many levels above the ground. Climbing on, we’ll reach the present day but we shouldn’t rest or pause too long. The tour won’t be over – this tour will never be over – for this is a house that will never be completed. Like all buildings, this arthouse has nooks and crevices hidden away that are rarely illuminated by the sun. In one of these nooks we might encounter paintings and drawings along similar lines to this: This charming work from our selection of drawings (appropriately titled Charmingly Finished; click here or on the drawing to see the full description) was sketched in 1823. The artist is unknown (it is initialled ‘W.T.C.’) but it provides a small insight into an overlooked subset of art history that first came to prominence in the 16th century. Known as singeries (from the French for ‘monkey tricks’), works depicting apes dressed as humans and acting in a human manner were first produced by Flemish artists; the idea was then taken up by painters and designers in France. Within in our house and its histories, the monkey has held numerous attributes. ‘Medieval and Renaissance man saw in the ape an image of his baser self. Thus it came to symbolize Lust, one of the seven deadly sins, idolatry and vice in general. In Christian art, with an apple in its mouth, it stood for the Fall of Man’ (Hall, 2001, p.10). A little further up the house, it was the artist who became most closely associated with the ape – both being known for their skill in imitation. This imitativeness was enshrined in the saying Ars simia Naturae – art is the ape of nature. In turn, this led to painters depicting ‘the artist as an ape, in the act of painting a portrait, generally of a female… This parody of man was extended to other human activities and apes were represented sitting at the meal table, playing cards or musical instruments, drinking, dancing and so on’ (Hall, 1989, p.22). The high point of anthropomorphised monkeys in art was during the Rococo period of the 18th century. Already a playful diversion in the arthouse, Rococo style was further enlivened by the introduction of monkeys in, for example, the work of Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), above. Although the vogue of Singeries largely died out in the nineteenth century, the monkey is still used (albeit without the anthropomorphism), for both parody and satire, in art today. Here on the top floor of the house we'll find monkeys in the work of Jeff Koons and far off in the distance we might find, beside a group of builders hastily constructing yet another staircase, something like this on the wall: And, as this is an imaginary house, we might find Banksy, spray can in hand, standing next to it.

References Hall, James (2001), Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art Hall, James (1989), Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed