|

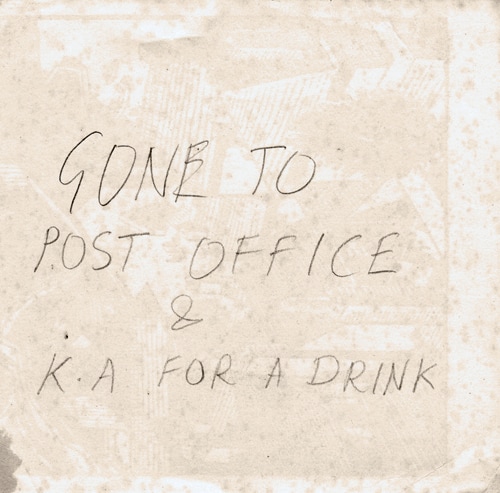

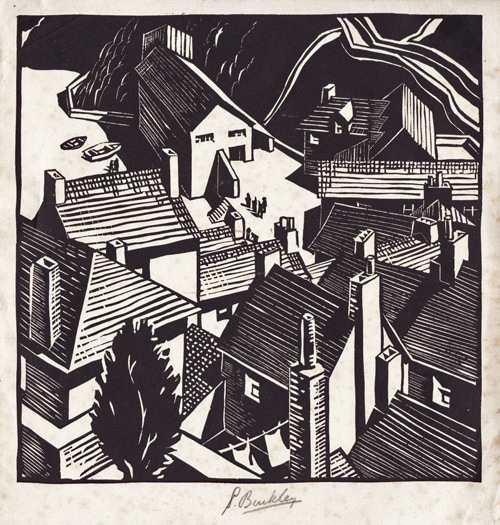

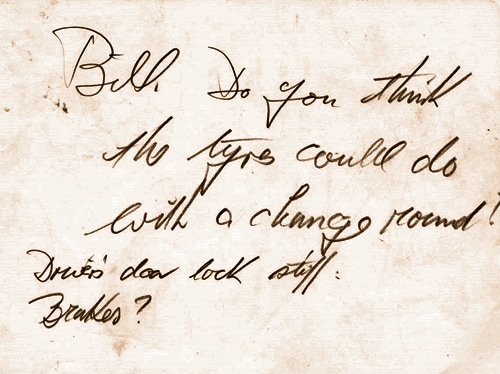

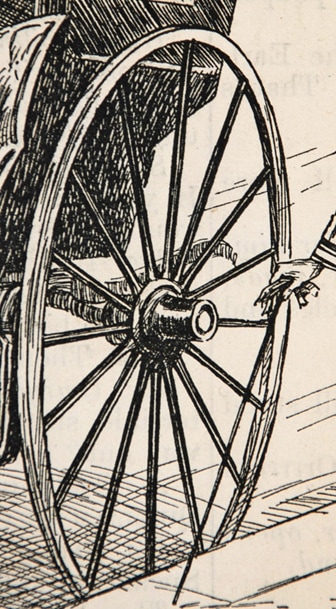

Today, we are blessed (or not) with a variety of convenient ways to communicate with each other. We can text, tweet and message and if the matter is urgent we can always fall back on ancient technology and make a phone call. In short, we can make contact and are contactable in return wherever we are at any time, instantly. It hasn’t always been this way. Back in the olden days (the 1960s or 1970s, say) if you wanted to communicate your whereabouts to the person you shared a house with, for example, the most expedient way would have been to leave them a note (look it up, kids). Here is just such a note and at first glance it appears to be nothing more than a mundane piece of domestic detritus. The author, as we can see, is off to the post office and the K.A. for a drink. We don’t need to bother Bletchley Park to conclude that in this instance, K.A. stands for Kings Arms. The note isn’t signed but I know who wrote it. I know because this is on the other side: The author was an artist called Sydney Buckley and the note was left for his sister with whom he shared a house at Cartmel in Cumbria. News of Buckley’s whereabouts was written on the reverse of this fine woodblock print titled Cornish Pattern which was designed and printed by Buckley perhaps in the 1940s or 1950s. The scene, typical of Cornwall, is of the rambling rooftops of a town edging on to a beach. In flavour and form it has the feel of Port Isaac, perhaps. It is showing some minor evidence of foxing and this may have existed when Buckley penned the note to his sister. Even so, it is a curious item to use to leave a note. Was there no other paper in the house? Buckley was a noted artist and printmaker (you can see two examples of his etched work on our website here and here) so it seems unlikely that the household was devoid of unused paper. This piece came from a larger collection of prints I bought about ten years ago, all by Buckley. There were ten or so copies of Cornish Pattern and I kept two. One is in mint condition with signature and title and the other is the copy illustrated above. Retained purely for its curiosity value, I was recently reminded of Buckley’s note when I acquired another small collection of artworks. These are all drawings and all by the same unknown hand (one of the many lost artists for whom the term ‘20th Century British School’ was invented). Here is one of the drawings: As we can see, it’s a competent, rapidly executed pencil sketch of a house. It is not fundamentally exciting as an image unless you happen to live in the depicted house, I suppose. Even so, the artist, for whatever reason, took the time and trouble to record the scene. The artist also used the reverse of the sheet for this: As the handwriting isn’t as clear as Buckley’s, here’s a transcript:

'Bill, do you think the tyres could do with a change round? Driver’s door lock stiff. Brakes?' Another note on the reverse of another artwork. It is possible with this example that the note preceded the drawing – at this remove there is no way of knowing for sure. But if the drawing came first, again, one has to ask why? Perhaps the artist dropped the car off at the garage and left the note on the car seat intending for Bill to read the message and then keep the note. This certainly didn’t happen – perhaps Bill didn’t turn the note over to see what was on the other side. Who knows? So many questions raised from two simple relics, each no more than forty of fifty years old, from a time before the age of instant communication. What, I wonder, did Buckley have to drink at the Kings Arms? And the enigmatic ‘Brakes?’ in the second message. Check the brakes? Fix the brakes? Sabotage the brakes? We’ll never know.

My life is a

You crawl through the

Slip across the

and into the reception room

You enter the place of endless persuasion

Like a knock on the

When there's

or more things to do

Who is that

You my companion

Run to the

on a burning

And it brings me relief

Pass through the

To find my intentions

round in a strange

state

I

There is no connection

A million points of

And a conversation I can't

Cast me off one day

To lose my inhibitions

Sit like a lap

on a matron's

Wear the nails on your

I woke up the

Stumbled in

The

went on and everybody screamed

The savage review

It left me

it warms my

to see that you can do it too

Total

Your

is so tender

Your

is like

on a

And it brings me relief

And it brings me relief

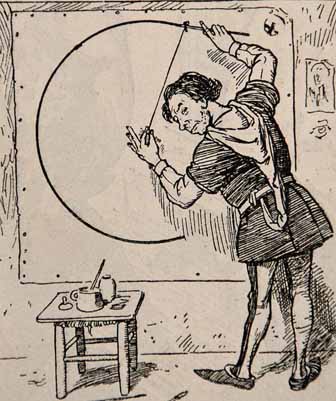

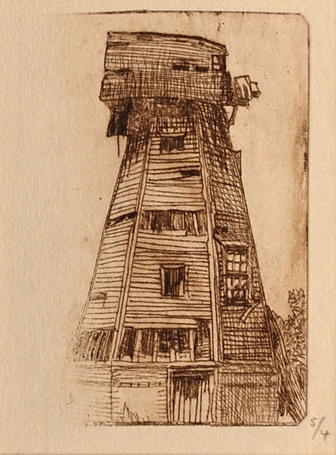

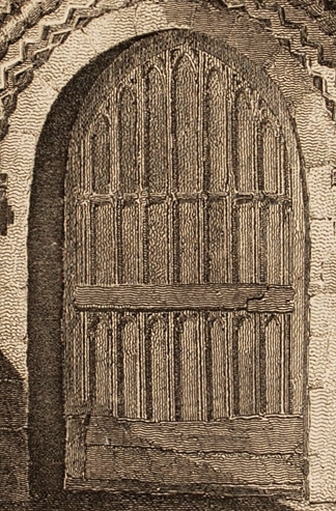

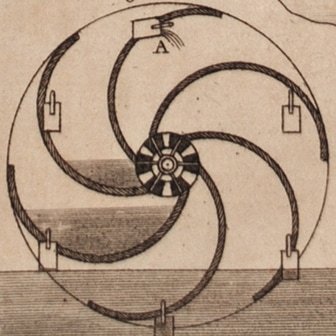

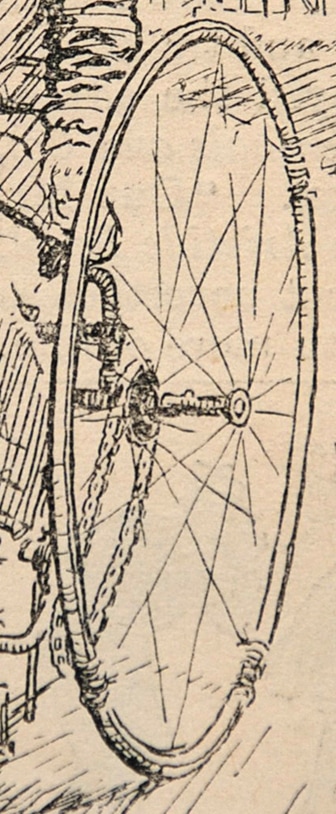

And it brings me relief The reputation of Karl Salsbury Wood (1888-1958) largely rests upon a remarkable series of paintings he produced between the late 1920s and his death in 1958. For almost thirty years Wood cycled around Britain in an attempt to visually record every existing windmill in the country. Wood’s plan was to publish a book titled The Twilight of the Mills containing his illustrations and written notes. In addition to being a talented (and clearly driven) painter, Wood was also a printmaker, as the small collection of etchings on our site illustrates (the full selection can be seen here). The subjects of the etchings reflect Wood’s interest in architecture and architectural details. Structures – castles, churches, inns and the ubiquitous windmills – are predominantly the focal point; the edges of the buildings straining up against the edges of the etching plate. A tree or two might act as the frame for a country church but it was unusual for Wood to record the bigger picture – the landscape the buildings exist within. The prints provide a useful insight into the way in which etchings are created. The etching process, though time-consuming, is relatively straightforward. A metal plate is coated in a layer of acid resistant wax, a design is then drawn on to the wax through to the metal plate and the plate is then immersed in acid. This bites away at the metal elements exposed by the artist’s design; the longer the plate is immersed the deeper the lines will be etched and the darker they will print. The etched image is constructed in stages (known as states), the various elements of the picture being worked on systematically until the finished image is arrived at. Windmill with Pigs (above) is clearly at a very early, rudimentary stage – just the outlines of the windmill and the pigs have been bitten. This print is numbered 1/1 which presumably means this is the first impression Wood took from the first state of the print. Here, Wood continues to develop a design in a third impression. As with Windmill with Pigs, major outlines were defined in the first impression, perhaps more detail was added to the windmill in the second and it is probable that the first elements of the sky were added in the third. States were completed, impressions were taken and the images continued to form and grow. Occasional mishaps clearly happened, too. The print above appears not to have been fully pressed as the left hand plate edge is entirely absent. Eventually, after many decisions regarding the location of the lines to be etched and the depth to which they should be bitten, a finished work of art was produced. Perhaps Wood made these etchings (based on the paintings and sketches he undertook on his journeys around the country) as a means of raising funds towards the publication of The Twilight of the Mills. Regrettably, as we discuss in the artist’s biographical notes here, the book was never published.

Click on the images to see each picture's description Round, like a in a spiral, like a within a Never ending or beginning on an ever-spinning Like a snowball down a or a carnival Like a carousel that's turning, running around the Like a whose hands are sweeping past the minutes of its And the world is like an silently in space Like the that you find in the of your mind Like a that you follow to a of its own Down a hollow to a where the sun has never shone Like a that keeps revolving in a half-forgotten dream Or the ripples from a someone tosses in a Like a whose hands are sweeping past the minutes of its And the world is like an silently in space Like the that you find in the of your mind that jingle in your pocket, words that jangle in your head Why did go so quickly? Was it something that you said? walk along a and leave their footprints in the Is the sound of distant just the fingers of your in a hallway or the fragment of a song Half-remembered names and but to whom do they belong? When you knew that it was over you were suddenly aware That the were turning to the colour of her A circle in a a within a Never ending or beginning on an ever-spinning As the images unwind like the that you find In the of your mind.

Johnny's in the Mixing up the I'm on the Thinking about the government The man in the out, laid off Says he's got a bad cough Wants to get it paid off Look out It's somethin' you did knows when But you're doin' it again You better down the alleyway Lookin' for a new friend A man in a coon-skin In a Wants eleven dollar bills You only got ten Maggie comes full of black soot Talkin' that the heat put in the bed but The tapped anyway Maggie says that many say They must in early May Orders from the Look out Don't matter what you did Walk on your Don't tie no Better stay away from those That carry around a fire Keep a clean Wash the plain clothes You don't need a weather man To know which way the Get sick, get well Hang around an inkwell Ring hard to tell If anything's gonna sell Try hard, get barred Get back, write braille Get jump bail Join the if you fail Look out You're gonna get hit But losers, cheaters Six-time users Hang around the Girl by the whirlpool is Lookin' for a new Don't follow leaders Watch the pawking metaws Ah, get born, keep warm romance, learn to Get dressed, get blessed Try to be a suckcess Please her, please him, buy gifts Don't steal, don't lift Twenty years of And they put you on the day shift Look out They keep it all hid Better jump down a Light yourself a Don't wear Try to avoid the scandals Don't wanna be a You better chew gum The don't work 'Cause the vandals took the

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed