|

I wandered lonely as a That floats on high o'er and When all at once a saw a A host of Beside the beneath the Fluttering and in the Continuous as And twinkle on the milky way They stretched in never-ending line Along the margin of a Ten thousand saw I at a Tossing their heads in The beside them danced; but they Out-did the sparkling in A could not but be gay In such a jocund company I and but little thought What the show to me had brought For oft, when In vacant or in mood They flash upon that inward Which is the bliss of solitude And then my with And with the

Click on the images to see each picture's description

Did I see you

in a

with your

in so much

I was almost there

at the

with her

in the

Did she

to tell you that

it was only a change of

up

up

with the

Did I see you

though it was not

And was some

in a

when you could understand

Did she

to tell you that

it was only a change of

up

up

with the

Will I see you

Will I only

As the days

will we lose our

Or fuse it in the

Did she

to tell you that

it was only a change of

up

with the

up

up

with the

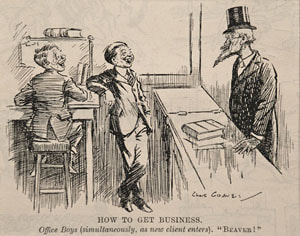

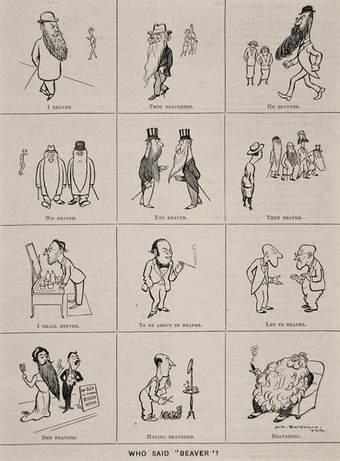

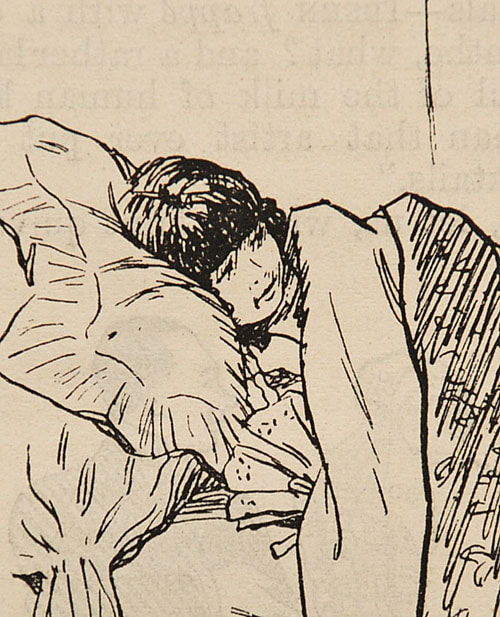

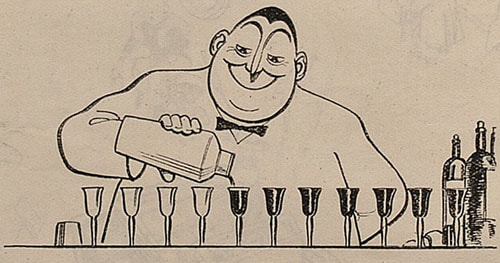

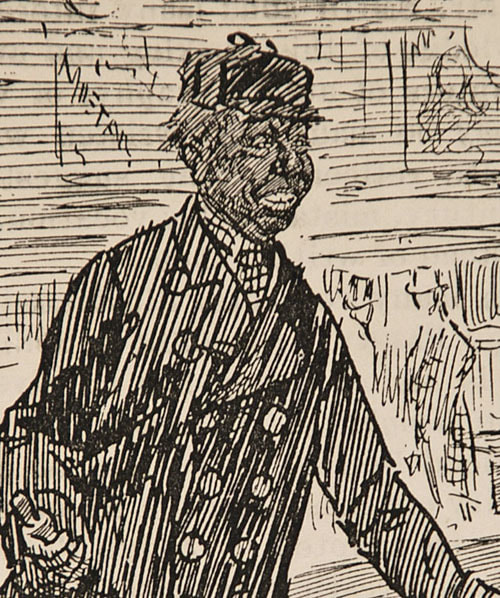

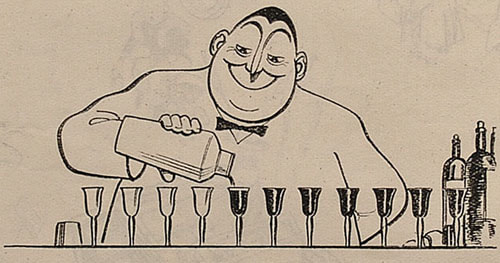

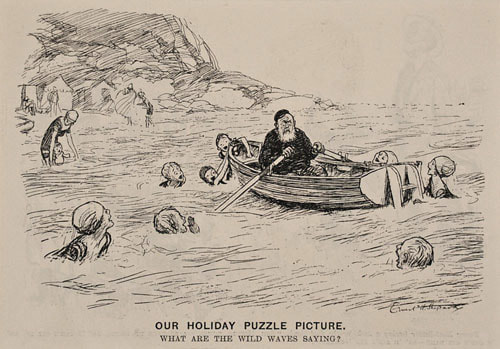

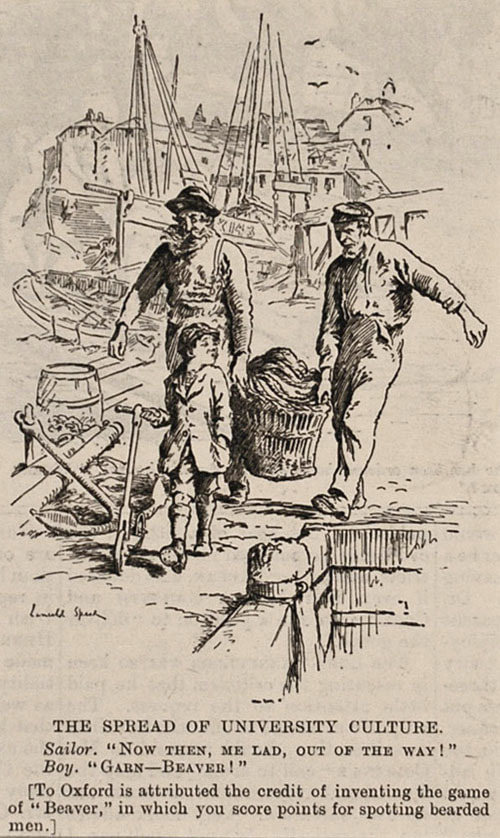

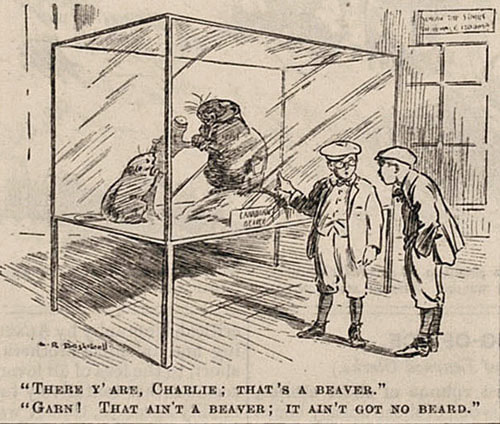

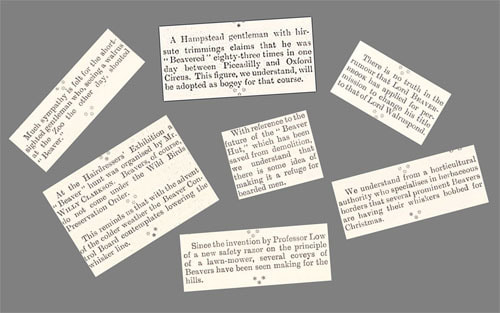

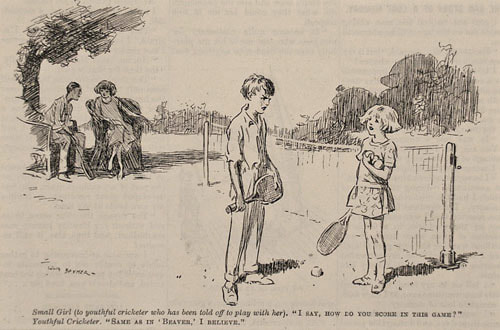

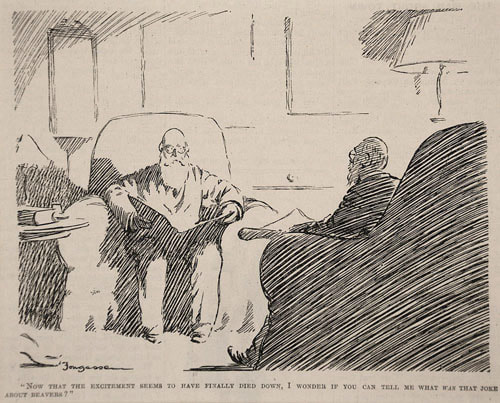

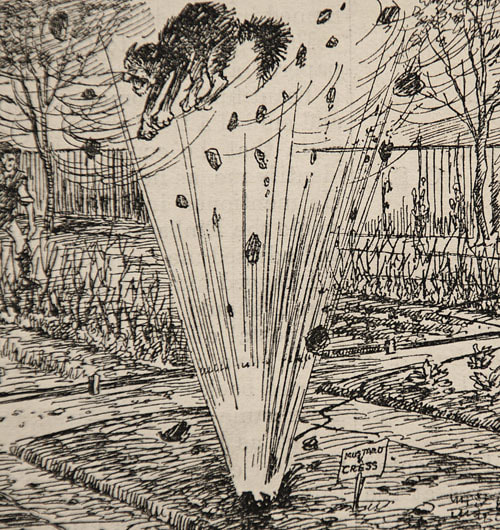

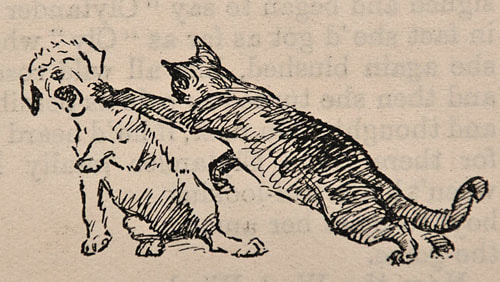

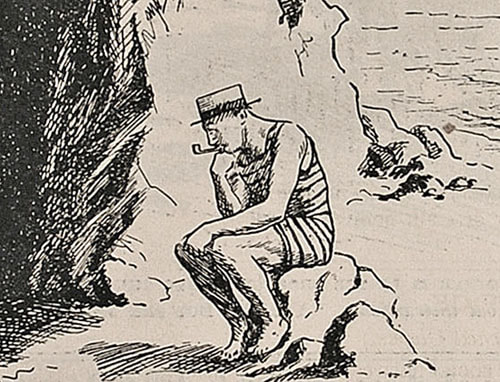

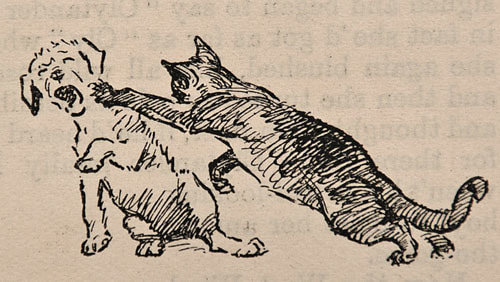

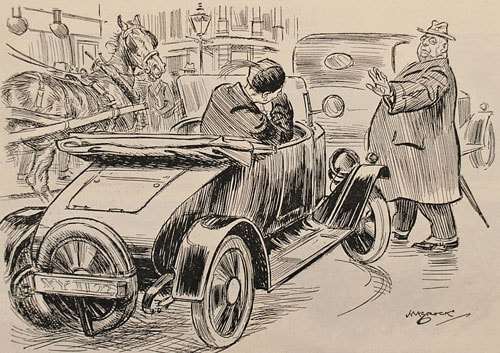

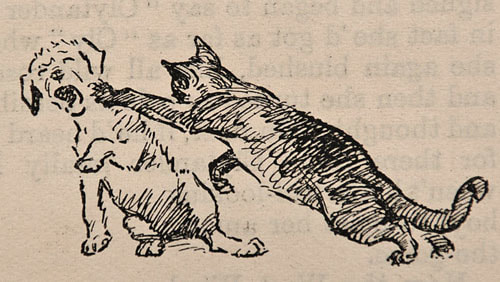

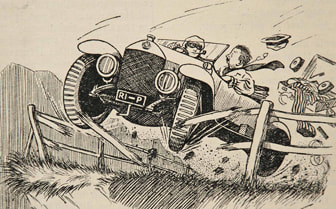

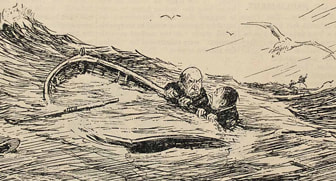

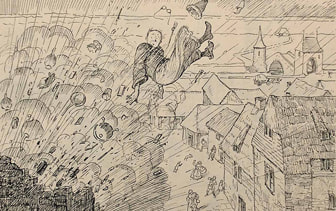

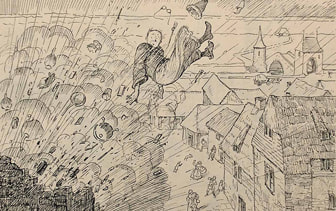

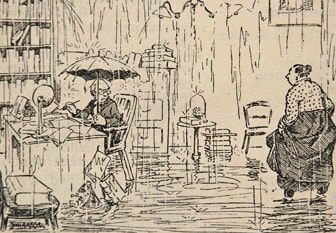

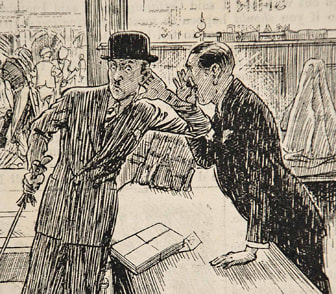

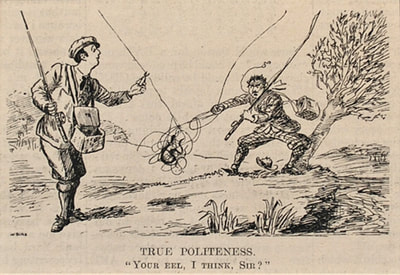

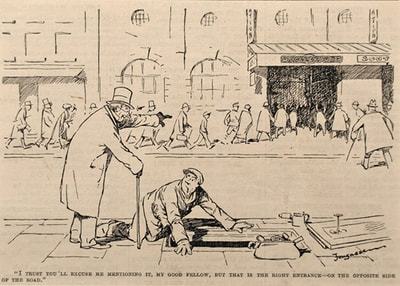

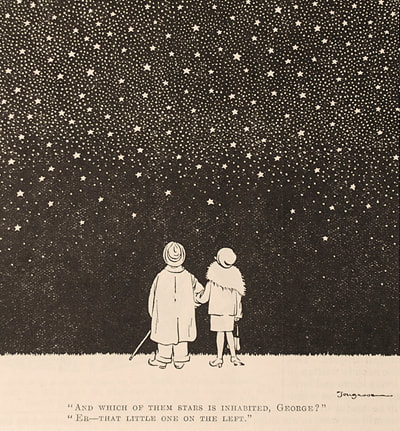

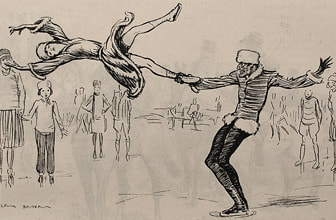

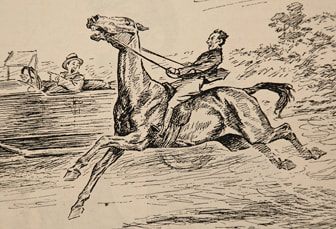

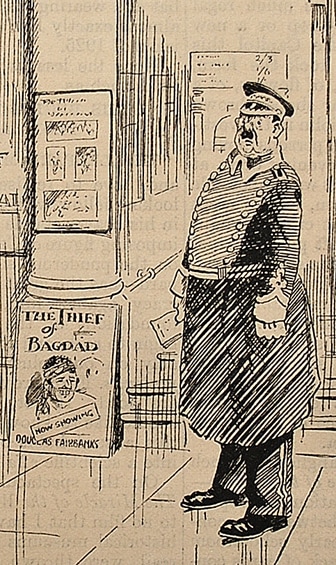

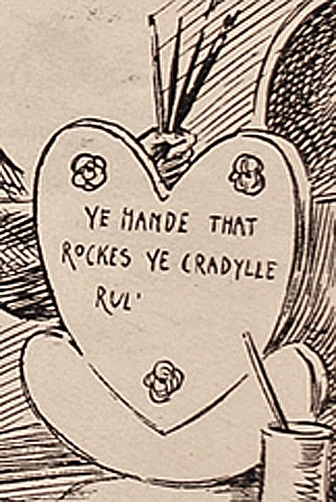

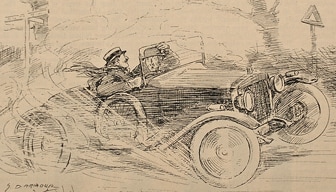

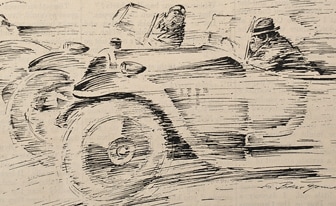

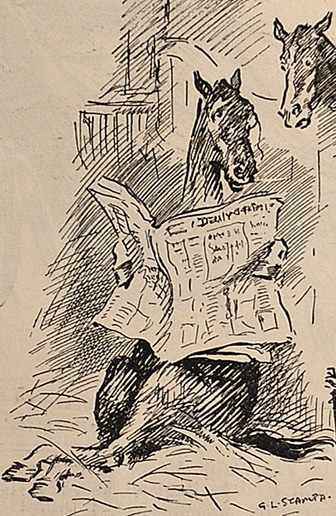

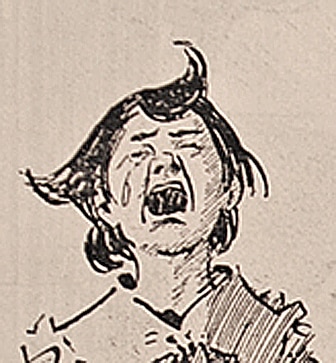

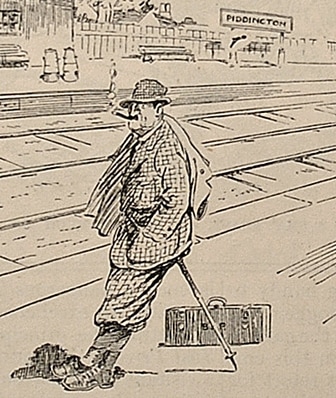

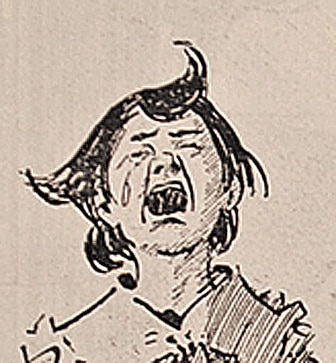

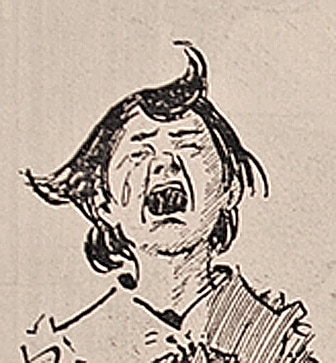

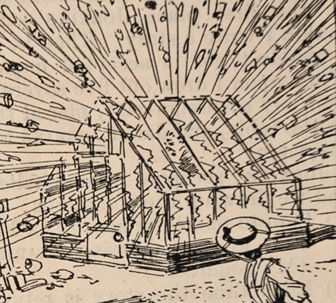

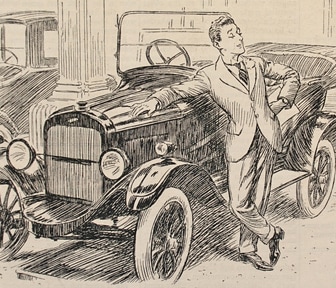

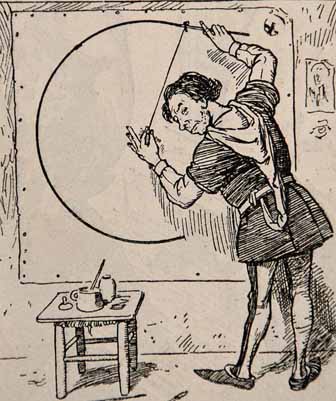

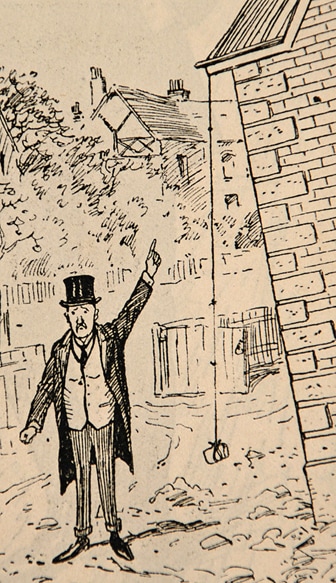

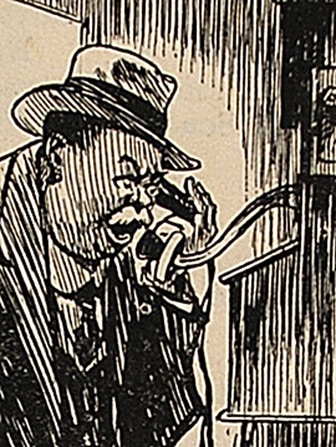

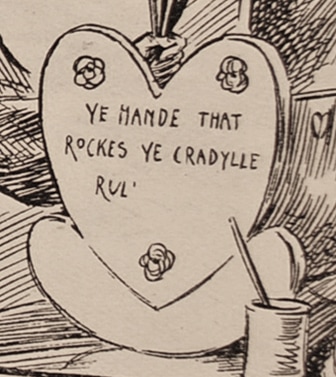

In August 1922 the following cartoon by E H Shepard appeared in Punch magazine. Captioned ‘Our Holiday Puzzle Picture. What Are the Wild Waves Saying?’, it shows a bearded man in a rowing boat surrounded by people bathing in the sea. Unless you are an expert in either the history of British beards or eccentric and short-lived crazes (or both) you might struggle to solve the puzzle. In 1922, no answer to the question was given in the magazine because no answer was needed. The contemporary audience would have known the solution all too well – all the bathers (the ‘wild waves’ as Shepard called them) are shouting ‘Beaver!’ at the hapless bearded boatman. Even the toddler at the sea’s edge, barely old enough to wade without the support of his mother, joins in with the ‘Beaver!’ chorus. For those sporting beards, 1922 looks to have been something of a trial. In 1959, some insight into the ‘Beaver!’ phenomenon was provided in The Spectator:  ‘When I was a boy there was a game called 'Beaver.' Except that it cost nothing to play and had rules which were simple to the point of inanity, it had little to recommend it; but for several months it enjoyed a nationwide vogue and provided music-hall comedians and humourists of the less subtle kind with an invaluable stand-by… It was a silly game. I don't know who invented it, or how it managed to catch on to the extent it did…’ As the cartoon below illustrates, Punch ascribed the invention of the game to students at Oxford University (the sub-caption reads ‘To Oxford is attributed the credit of inventing the game of “Beaver” in which you score points for spotting bearded men.’).  During the years of its publication, many odd and now-forgotten aspects of British life were reflected in the pages of Punch; ‘Beaver!’ did not escape the attention of those who wrote and drew for the magazine. Cartoonists including H M Bateman (left) and Leonard Brightwell (below) responded to the fad. ‘Beaver!’ also provided the impetus for a number of entries in the magazine’s Charivaria column. The rules may have been simple but as an article on The Atlantic website describes, ‘Beaver!’ was popular enough to provoke some enterprising soul to publish a book detailing the rules of the game (there is a copy in the British Library). ‘Beaver!’ was played by two people each attempting to be the first, upon sighting a bearded man (or woman – the elusive Queen Beaver), to call out ‘Beaver!’ The scoring system was based on that used in tennis as Lewis Baumer’s cartoon below illustrates. Mis-beavers – calling out ‘Beaver!’ only to discover that the poor beavered quarry was beardless – incurred a double-fault. We can only speculate as to why the word ‘Beaver’ was chosen as the game’s trigger. Beards and beavers are, of course, both hairy and there is a satisfying alliterative connection between the two words. Furthermore, beaver is also the name of the lower portion of the face guard of a helmet (Oxford English Dictionary). If we are to gauge the popularity of the game by its appearances in Punch, the ‘Beaver!’ fad seems to have lasted only a few months. Speed’s cartoon attributing the creation of the game to Oxford University was published in July 1922 (the craze would have been extant before this date, of course; how long before is not known). By the following January, Fougasse (below) had one bearded gentleman asking his similarly hirsute friend, ‘Now that the excitement seems to have finally died down, I wonder if you can tell me what was that joke about beavers?’ Clicking on the cartoons will take you to each piece’s full description. Click here for biographical details of the Punch cartoonists. Links to Sources The Atlantic (2010), Beaver! The Spectator (1959), Beards and the British, by Stria

Click on the images to see each picture's description

Well, now then

I've seen your

And it's like

And it

And out come all these words

Oh, there's a

A side I much prefer

It's one that

and

Remember

in the

yeah

To

And it was

and

Oh, but it's right hard

to remember that

On a day like today

when you're all

And you've got the

Well, know then

Oh, I'm

aren't I?

I

as much

'Cause you turned over there

that

The one that I can't

Well, can't we

and

Remember

in the

yeah

To

And it was

and

Oh, but it's right hard

to remember that

On a day like today

when you're all

And you've got the

And yeah I'm sorry I was late

But I missed the

And then the

And I can't be

to carry on

that reoccurs

Oh, when you say I don't care

But of course I do, yeah

I clearly do

So

and

Remember

in the

yeah

To

And it was

and

Still it's right hard

to remember that

On a day like today

when you're all

And you've got the

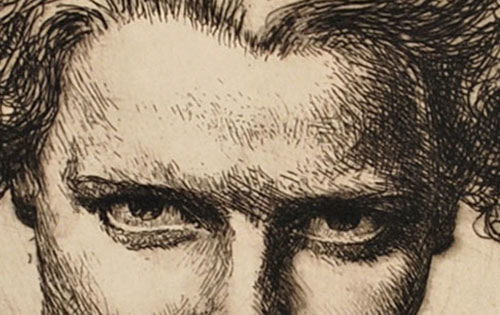

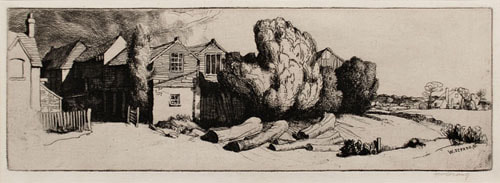

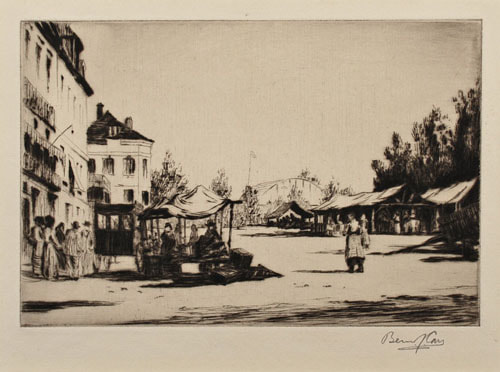

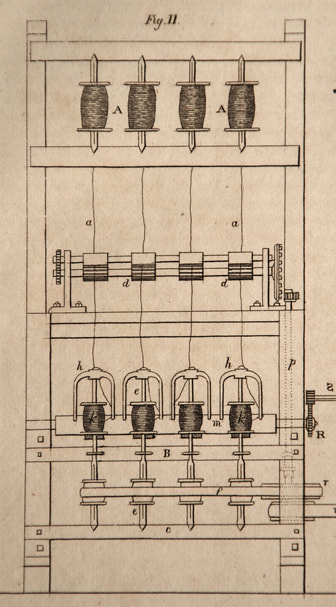

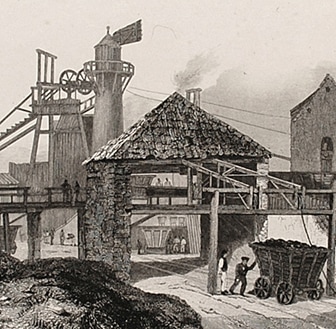

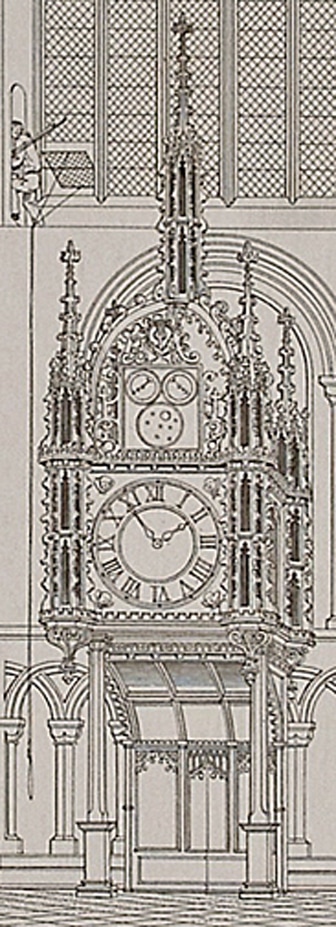

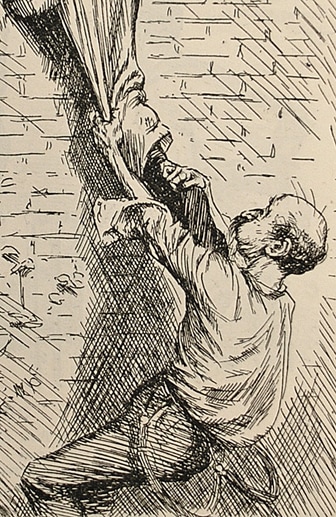

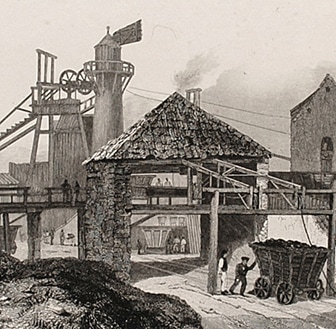

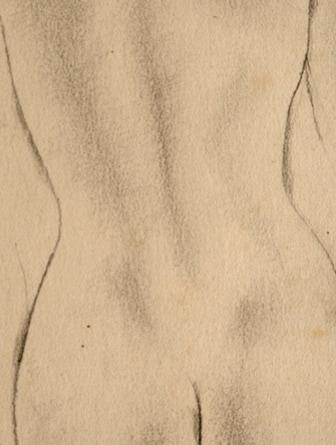

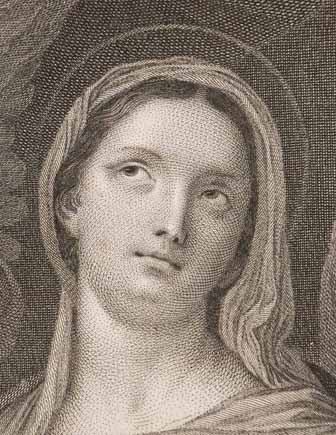

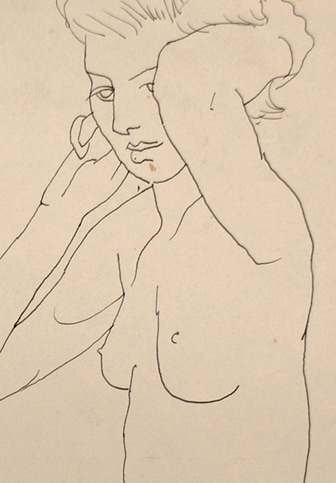

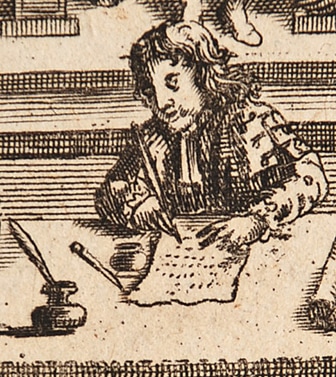

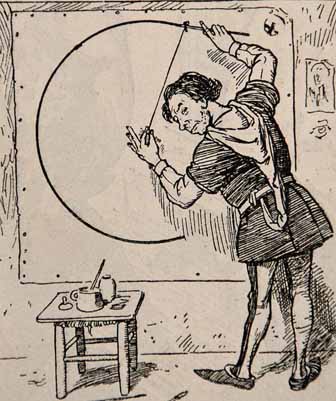

Etching as an artistic medium can be dated back to the beginning of the sixteenth century. The earliest dated etching is Girl Bathing Her Feet by Urs Graf of 1513. Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Albrecht Altdorfer (1480-1538) were early masters of the new technique which flourished on the continent as the century progressed. During the following century, Rembrandt (1606-1669) embraced the relative freedom of expression that the technique offered to produce over 300 original etchings. Thereafter, however, ‘for the century and a half that followed the death of Rembrandt the art of original etching was little practiced and less understood’ (Hind, p.312). During the early nineteenth century etching held a minor position in the arts in Britain. Considered something of a ‘lost’ technique, it was little utilised until the formation of the Old Etching Club in London in 1838. Members of the Club, and the Junior Etching Club that developed from the original group, were principally concerned with producing etchings to illustrate works of literature in an effort to subsidise their primary pursuit of painting. For much of the nineteenth century etching was considered a minor element of the artistic canon; indeed, the Royal Academy gave greater prominence to engraved reproductions of paintings than it did to original prints. This dismissive attitude was to change due primarily to the work of Francis Seymour Haden (1818-1910) and his brother in law James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). These two men, through a combination of example and promotion, provided the platform for a renewed interest in etching. In the mid-1850s, Whistler spent three years in France where he had been introduced to the work of Charles Meryon (1821-1868), Félix Bracquemond (1833-1914) and Charles Jacque (1813-1894), the leading French etchers of the time. In 1858 Whistler moved to London where, influenced by the work he had seen in Paris, he began a series of etchings of scenes along the River Thames. By the late 1870s, the Old Etching Club had largely ceased to function as anything other than a social group. Haden, a surgeon and talented etcher, proposed the formation of a new society dedicated to promoting etching as an important medium in its own right. The first meeting of the Society of Painter-Etchers was held in 1880 with Haden its President. He gave the group its original motto: Ne Desilies Imitator – ‘Do not stoop to be a copyist.’ In this phrase lay Haden’s central aim – that printmakers should produce original works and, by extension, the art of etching should come to be viewed as a valid and important artistic medium. Eight years after its formation the Society was granted a Royal Charter and six years later, in 1894, Haden was knighted for his service to the arts. The influence Haden exerted over the Society was immense. He promoted the idea that an artist could convey as much with empty space as he or she could through the use of a multitude of unnecessary (as Haden saw it) bitten lines. He also believed that each artist should, where possible, draw onto pre-prepared plates, directly from nature. To ensure that all aspects of the process could be overseen by the artist, Haden further suggested that etchers should master the techniques of the press to enable them to print and proof their own work. Demand for original etchings grew steadily through the later years of the nineteenth century. This growing interest was encouraged by the efforts of Phillip Gilbert Hamerton (1834-1894), ‘the chief publicist for the British [etching] revival’ (Lang and Lang, p.42). Hamerton, himself a keen etcher, believed that the biggest obstacle to the acceptance of etching as a valid art form was a largely ignorant public. He endeavoured to rectify this through the publication of Etching and Etchers (1868) in which he lauded the efforts of Whistler and Haden (‘Here is a book written to increase the public interest in an art we [Haden and Hamerton] both love’, was the rallying first line of the book’s dedication to Haden). Furthermore, Hamerton argued against the prevailing view that the technique was a purely illustrative medium. Published at a guinea and a half and much to Hamerton’s surprise, the book rapidly sold out. The success of Etching and Etchers confirmed Hamerton’s belief that an educated public could lead to an informed and enthusiastic market. Hamerton’s subsequent publications (The Portfolio, The Etcher and English Etchings published between 1879 and 1891) continued to supply an ever more interested public with information about works by the growing spectrum of artists working in the medium. Throughout the first decade of the twentieth century as the number of practitioners increased so the demand for original etchings also grew. In 1911 The Print Collector’s Quarterly was launched ‘as a response and a stimulant to the growing demand’ (Lang and Lang, p.51). The market for original etchings increased rapidly, reaching its zenith in the decade immediately after the First World War. Print auctions at Sotheby’s increased from six to twenty four sales a year during the second half of the 1920s and the prices for individual works similarly escalated. Muirhead Bone’s Ayr Prison, originally published in 1905 for £2.2.6, sold for £365 in 1929; David Young Cameron’s Five Sisters, York Minster set the record price for a print by a living artist in 1928 when a collector paid £660 for a copy.

Soon after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 the market for original prints collapsed. The pioneering work of Whistler and Haden coupled with Hamerton’s promotional zeal produced a period of unmatched popularity and recognition for a previously overlooked and neglected technique. Due to the diminishing market, the production of original etchings slowed and has never returned to the levels of the 1920s. The craze for original etchings may now be a century old but the medium endures as does the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers. Today it is called the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers and it continues to hold exhibitions showcasing artists working in this most expressive and striking medium. This essay is a modified and abridged version of the author’s introduction to the catalogue for the exhibition Whistler, Haden and the Rise of the Painter-Etcher, held at the Hatton Gallery, University of Newcastle in 2001. We discuss the etching technique in more detail in our short article about the work of Karl Salsbury Wood here. More information about the work and history of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers can be found on their website. Sources and further reading Farr, D (1978), English Art 1870-1940, Oxford University Press Furst, H (1931), Original Etching and Engraving, An Appreciation, T. Nelson and Sons Garton, R (1992), British Printmakers 1855-1955, Garton and Co Gray, B (1937), The English Print, Adam and Charles Black Heard, A (2001), Whistler, Haden and the Rise of the Painter-Etcher, University of Newcastle Hind, A M (1923), A History of Engraving and Etching from the 15th Century to the Year 1814, Constable and Company Lang, G E and Lang K (1990), Etched in Memory, The University of North Carolina Press Laver, J (1929), A History of British and American Etching, Ernest Benn Ltd Rowland, S (1940), The Decline of Etching in Apollo, July 1940

Click on the images to see each picture's description

You

from crumbling

watching

turn to

Filming helicopters

in the

from way above

Got the

in you

Got the

in you

You've been

here forever

and you just can't say

Kisses on the

of the

You've been

them in hollowed out

left in the

Got the

in you

Got the

in you

You've been

here forever

and you just can't say

Your

My

Your

My

Go and sneak us through the

is rising up on your

Oh please

Come out and

I know you want me

Come out and

Sharing all you secrets

with each other since you were

with the

that she gave you

clutched in your fist

Got the

in you

Got the

in you

You've been

here forever

and you just can't say

You've been

here forever

and you just can't say

When you're all alone

I will

When you're

I will be there too

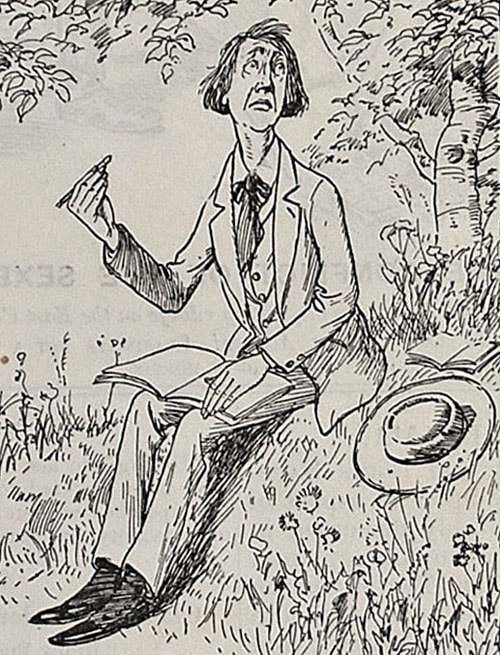

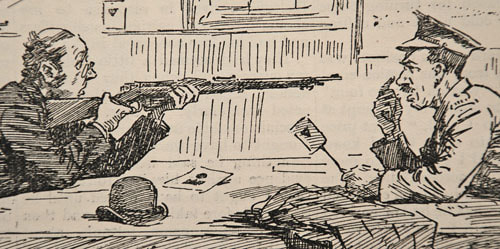

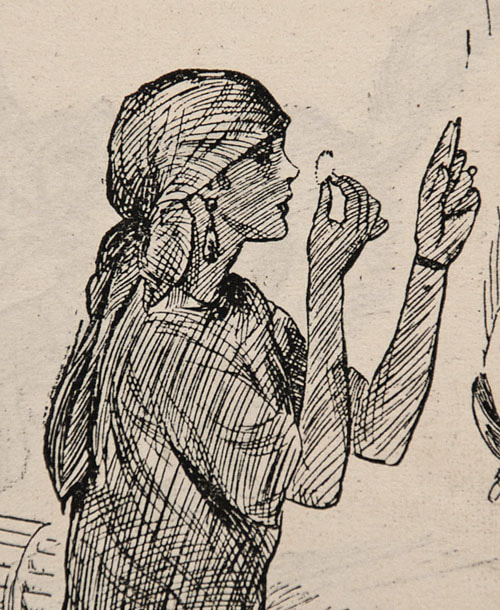

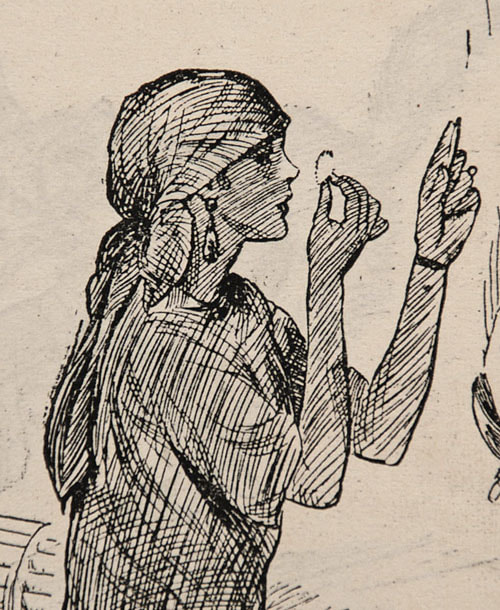

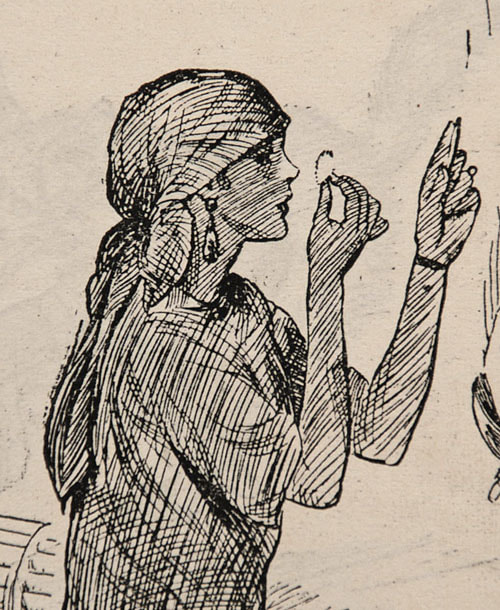

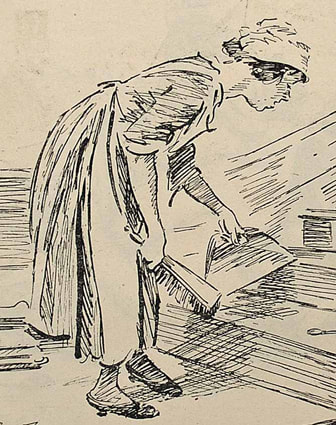

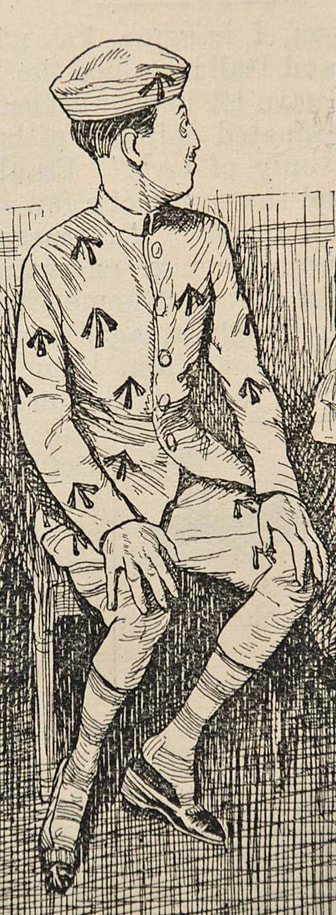

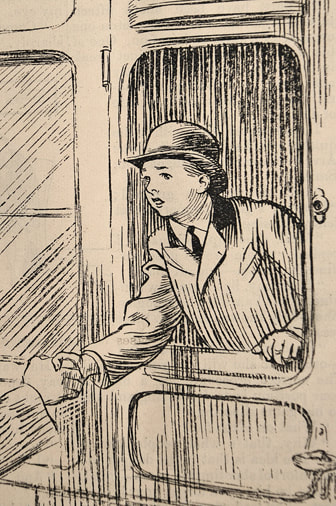

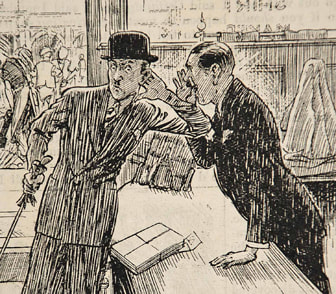

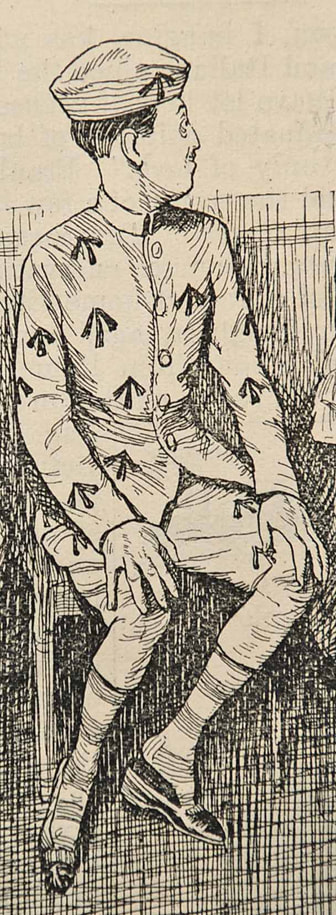

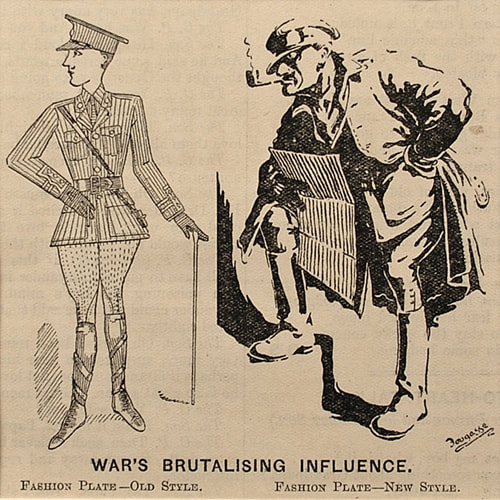

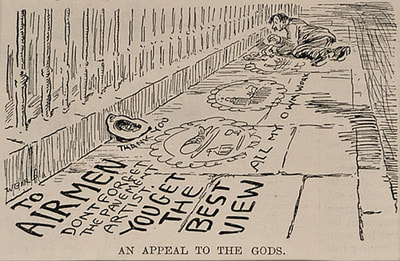

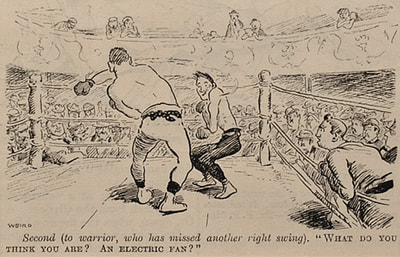

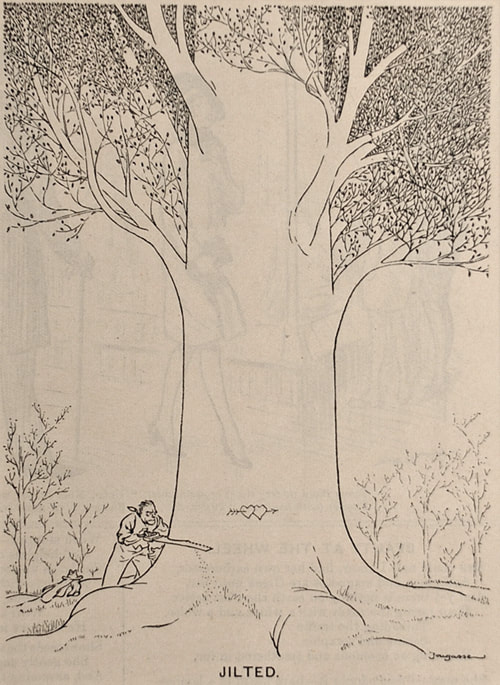

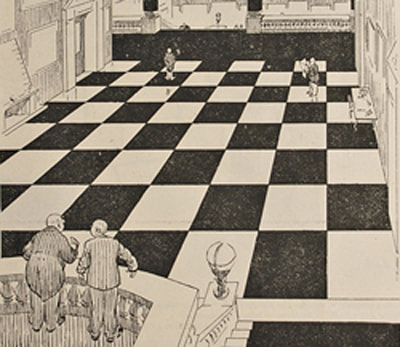

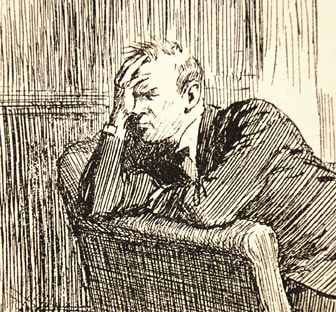

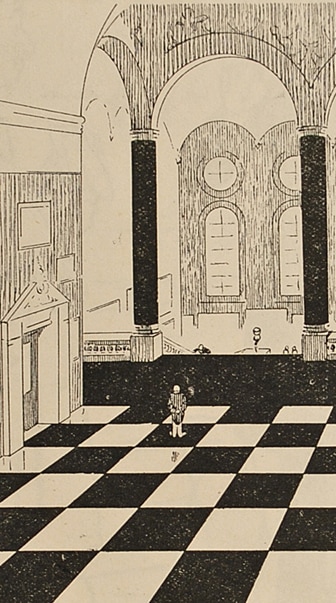

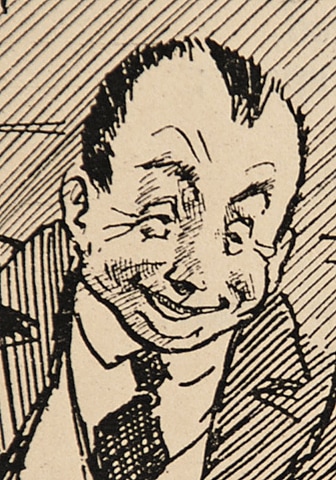

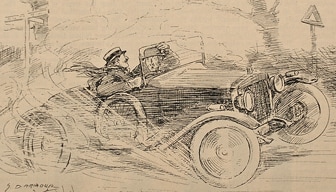

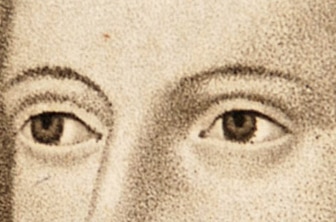

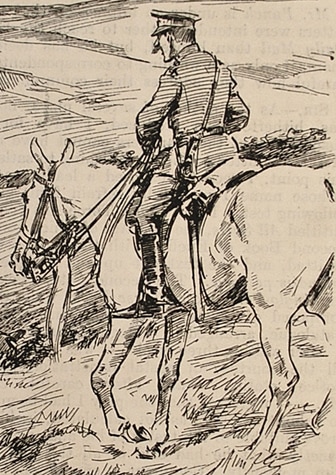

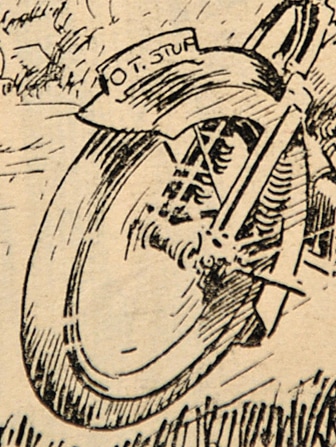

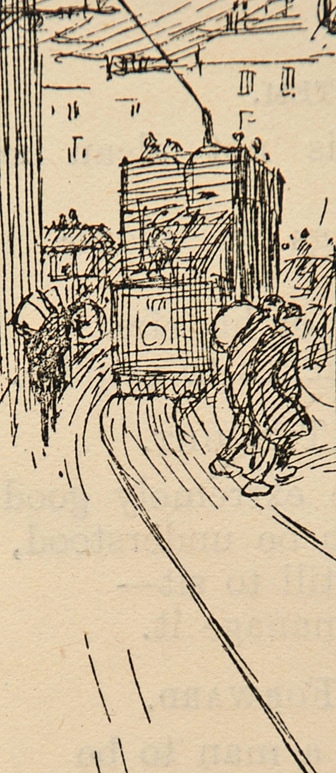

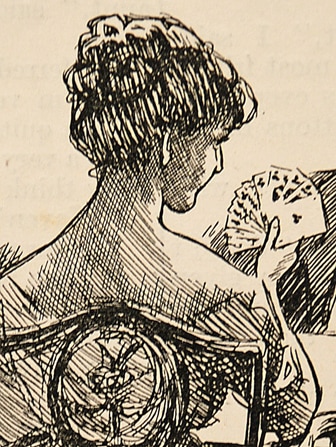

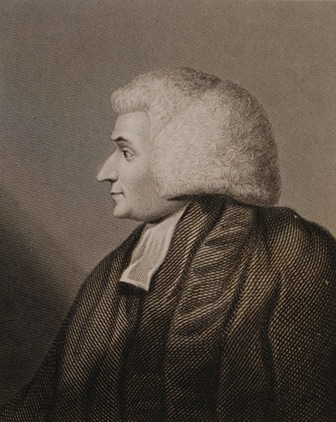

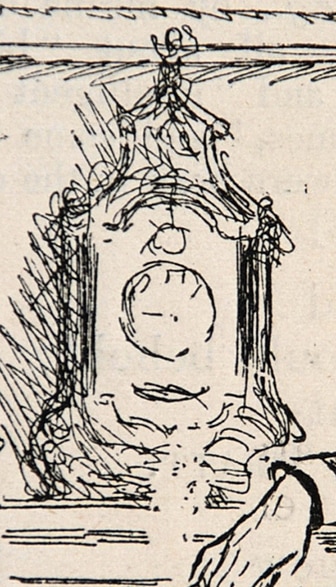

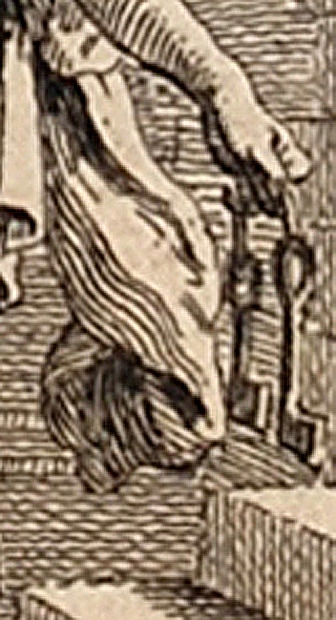

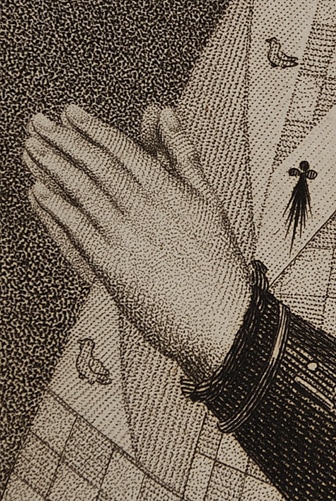

During the First World War, Kenneth Bird was hospitalised following an injury to his spine sustained at Gallipoli in 1915. Prior to the war, Bird had been an instructor with the Artists’ Rifles and had worked at the Rosyth naval base. ‘Horribly wounded… [he] realised he would have to find something to do which would not overtax him physically.’ (Anderson, p.156). Having earlier attended evening classes in art at Regent Street Polytechnic, that ‘something’ was cartoons and illustrations which Bird submitted to numerous publications. His first cartoon for Punch, below, was published in 1916. When War’s Brutalising Influence was published there was another artist submitting to Punch who signed his work ‘W. Bird’. For this reason, Kenneth Bird adopted the name ‘Fougasse’, a small improvised land mine of the type he would have encountered during the war, for his cartoons, illustrations and designs. The other cartoonist wasn’t actually a Bird at all. ‘W. Bird’ was Jack Butler Yeats, author, Olympic medallist and Ireland’s most influential artist of the twentieth century. As can be seen in the images above, Yeats’ submissions to Punch are characterised by a free-flowing, loosely handled style. This approach, so expressively forceful, vibrant and modern when employed by Yeats in colour on canvas, looked, to a contemporary audience, hasty, sketchy and somewhat amateurish in black and white. As Price (p.209) related, ‘Townsend and Seaman [Punch’s Art Editor and Editor at the time] continued to print… Bird, though many readers must have brought pressure on them, attacking Bird’s drawings as not representing reality.’ In fact, Bird’s drawings did represent reality – they just didn’t represent it in the manner to which Punch readers had become accustomed, as the two cartoons below (Yeats left; G D Armour, a contemporary Punch cartoonist, right) illustrate. Leaving aside the merits or demerits of the humour, Yeats’ cartoons are published sketches whereas Fougasse’s are coherent and fully formed designs. They possess an intrinsic strength of line coupled with the parsimony of a dedicated minimalist to show just enough to carry the joke or make the point. Whether it was two fellows negatively silhouetted against a hatched hedge or two others before an Underground station, Fougasse clearly understood that, when working in monochrome, sparseness can be strength. They were modern, too, and would have seemed so to contemporary eyes. There is a timeless element to Fougasse’s more successful cartoons. If you’d have found Jilted, above, funny in 1926 there is no reason not to find it funny today. It doesn’t require an understanding of time and place for the laugh; all the viewer needs is an emotional connection to the subject. Such a work is relevant today in part because it deals with a universally understood situation and also because of the strength of the cartoon’s design. This design ethic runs through Fougasse’s work – he instinctively knew where to place a line and, crucially, when to leave a line out. He also understood the impact bold contrast could produce. In 1937, Fougasse was made Art Editor of Punch and continued to publish his own drawings. Over time, his technique simplified further, becoming even more stripped back and to the point. His mature style was employed to great effect during the Second World War in the ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ propaganda posters he designed for the Ministry of Information. In 1949, Fougasse was made Punch Editor, the only cartoonist in the history of the magazine to hold the position.

Yeats, too, continued to submit ‘W. Bird’ cartoons to Punch until 1941. Away from his published drawings, his individual, expressionist paintings ‘helped articulate a modern Ireland of the twentieth century’ (Brennan, 2007). Additionally, he published novels, wrote plays and designed sets for the Abbey Theatre, Dublin. In 1924, following the establishment of the Irish Free State, Yeats won the country’s first medal at the modern Olympic Games. The discipline was Painting and Yeats was awarded the silver medal for a work titled The Liffey Swim. Painting was one of the Arts categories which featured at Olympic competitions from 1912 to 1948. Our full selection of Punch cartoons can be seen here. Our biographies of Bird, Yeats and other Punch cartoonists can be seen here. Sources and further reading Anderson A (1982), The Man Who Was H M Bateman, Webb and Bower Brennan S (2007), A speech delivered at the National Gallery of Ireland Bryant M and Heneage S (1994), Dictionary of British Cartoonists and Caricaturists 1730-1980, Scolar Press Price R G G ((1957), A History of Punch, Collins

Click on the images to see each picture's description

You

I was

The only one

who got your

And for a while

I believed the

that you

But I've been

at the things you do

the way you wanted me to

How, how

You

I

Now that I found where you're at

It's

Well

It's

You only came for a

Even though you're really not my

I didn't think that you'd

me

like you do

How, how

You

I

Now that I found where you're at

It's

Well, I've been

I'll tell you what I see

at the things you do

No, you can't fool me

the way you wanted me to

How, how

You

I

Now that I found where you're at

It's

You

I

Now that I found where you're at

It's

Well

Click on the images to see each picture's description

Little

Little

will guide them to me

My

is all

My

is all

If they find me

They'll not take me for a

Let me be

let me

and dream of

Oh, I'll

to any sound of

Every

a seeking

I can't keep my

open

Wish I had my

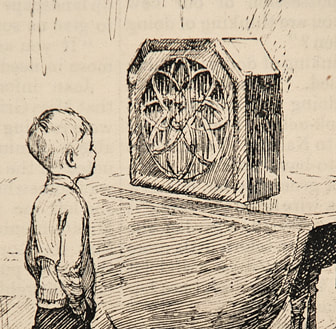

I'd tune into some friendly voices

Talking 'bout stupid things

I can't be left to my imagination

Let me be

let me

and dream of

Oh, their breath is

And they smell like

And they say they take me

Like

heavy with seed

They take me deeper and deeper

Click on the images to see each picture's description

It's

outside

And the

peeling off my

There's a

In a

Now the

And I'm wondering what I'm doing in a

like this

There's a knock on the

And just for a

I thought I remembered you

So now I'm

Now I can

for myself

About little deals and issues

And things that I just don't understand

Like a

lie that

Or a

at times

I don't think it meant anything to you

So I

It's the friend that I'd left in the hallway

Please

A

on a

near the

You know I hate to

But are friends

Are they?

Only

And now I've no one to

So I find out your reason

For the

and

And it

and I'm lonely

And I should never have tried

And I missed you

So it's

to leave

You see it meant everything to me

Click on the images to see each picture's description

on

of

That will bring you

to me

I'll never be free

The

I see

As I

for your

Though my

are

My

are

by fate

With clay at the

As I

and

What

I see

In

she

on a

With Jesus at the

The

that beg

Her

along the way

As she comes to me

Now as the

One

left to

the way

to the morning

She comes to me

To

up my darkest day

And the world fades away with her

on

of

That will bring you

to me

I'll never be free

The

I see

As I

for your

Click on the images to see each picture's description

I heard she drove the silvery

Along the empty

last

With

like

No I haven't see the

for some

her

from the red brick

Just like a

as she moves

And back

at half past two

With a

folded outside the loo

falls like Elvis

Oh no, no sugar tonight

Out on the

Dim all the

and

coloured

again

And

Don't forget to

me

Don't forget to

me

Don't forget to

me

Hobart

don't you think that it's

On this

with the

in my

And

Don't forget to

me

Don't forget to

me

Don't forget to

me

Hobart

don't you think that it's

The

in my hand

The

down the

falls like Elvis

Oh no, no sugar

Out on the

Dim all the

and

coloured

And

Don't forget to

me

Don't forget to

me

Don't forget to

me

Hobart

don't you think that it's

On this

with the

in my

Oh no, no sugar tonight

Don't forget to

me

Oh no, no sugar tonight

Don't forget to

me

Oh no, no sugar tonight

Don't forget to

me

Don't forget to

me

Click on the images to see each picture's description

I am a

And I

and I

I

through the

I see the

come out of the

Yeah they're

in a hollow

You know it looks so good tonight

I am a

I stay under

I look through my

so

I see the

come out tonight

I see the

and hollow

Over the

a

And everything looks good tonight

Singing la, la, la, la...

Get into the

We'll be the

We'll

through the

tonight

We'll see the

ripped

We'll see the

and hollow

We'll see the

that shine so

The

was made for us tonight

Oh the

How, how he

Oh the

He

and he

He looks through his

What does he see?

He see the sided hollow

He sees the

come out tonight

He sees the

ripped

He sees the winding

And everything was made for you and me

All of it was made for you and me

'Cause it just belongs to you and me

So let's take a

and see what's

Singing la, la, la, la...

Oh the

He

and he

He sees things from under

He looks through his

He sees the things he knows are his

He sees the

and hollow

He sees the

at

He sees the

are out tonight

And all of it is yours and

And all of it is yours and

So let's

and

and

and

Singing la, la, la, la...

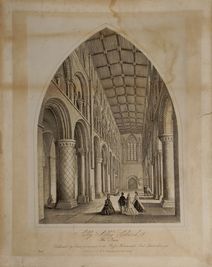

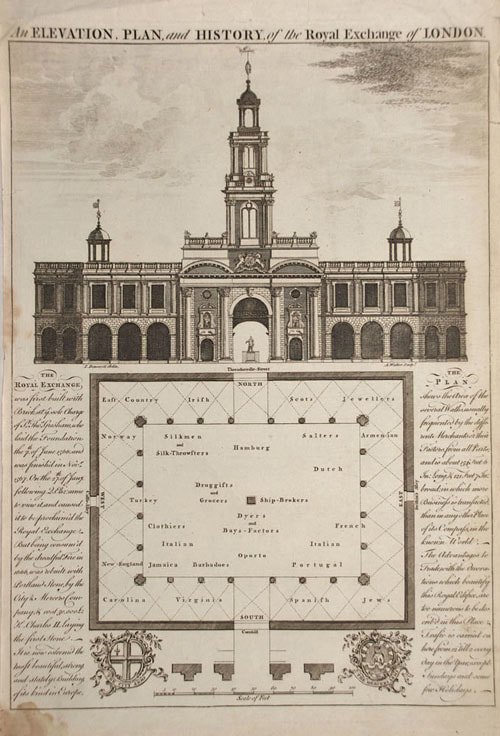

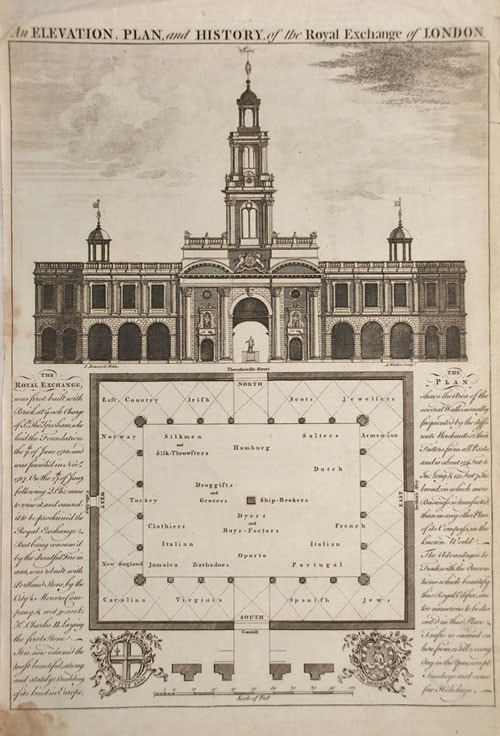

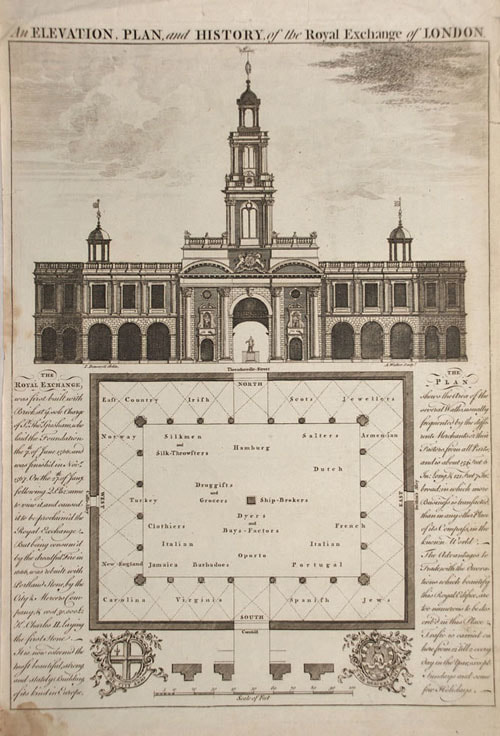

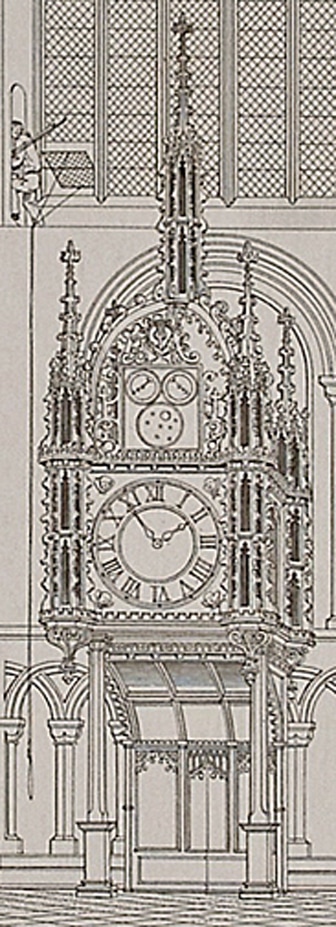

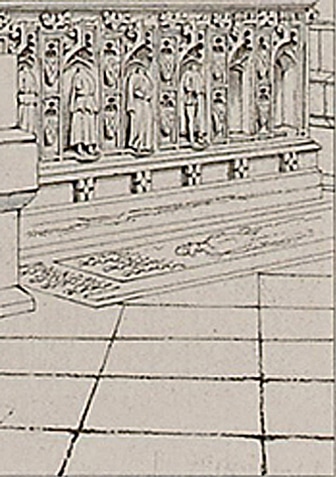

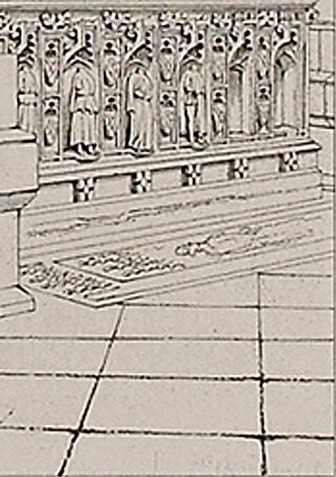

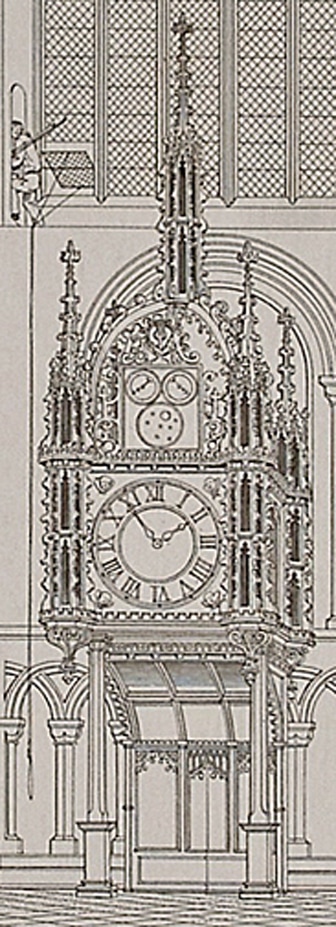

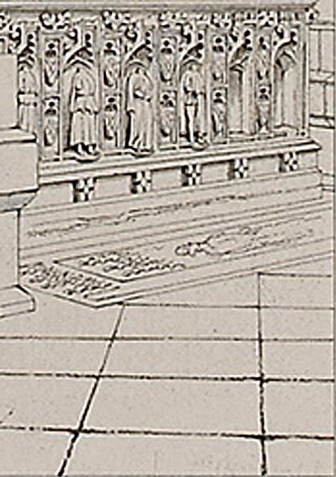

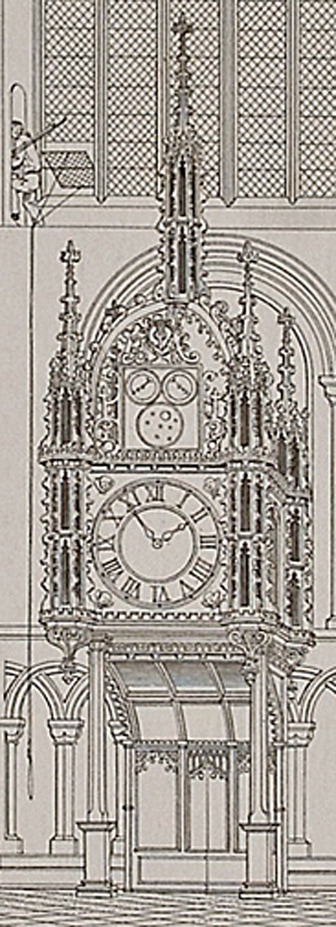

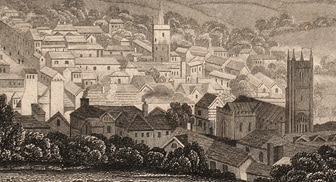

In 1290, Eleanor, Edward I’s Queen died at Harby near Lincoln from a fever. The King, heartbroken and in mourning accompanied Eleanor’s body (minus her internal organs which were interred at Lincoln) on its slow procession to London for burial at Westminster Abbey. In commemoration of his late Queen, Edward had twelve memorial crosses erected at the points where the body had rested each night on its journey south. The cortege’s progress had been slow, being ‘dictated by the royal houses and monasteries where the king could spend the night’ (Aslet, p.323). The resulting twelve crosses were the work of different designers and masons and were not uniform in style or size. It is safe to assume that the grandest of the twelve were at Cheapside and Charing Cross in London if only because the accounts from the time indicate that these were the most expensive constructions (Alexander and Binski, p.362). Some speculation is necessary when discussing the Eleanor Crosses because, of the twelve that were built in the 1290s, only three – at Waltham Cross, Hardingstone and Geddington (below) survive today. The monument now outside Charing Cross station, incidentally, is Victorian; it is not a replica of the thirteenth century cross, nor is it at the site of the original. In 1290, Geddington, home to royal hunting lodge, was the third halt, after Grantham and Stamford, on the journey to London. Today, this fine memorial looks just as it did when this engraving was published in 1805 (you can see the full item description here). Moreover, apart from some natural weathering, the cross looks the same as it did when it was built around 725 years ago.

Geddington’s longevity and relative intactness is all the more impressive when viewed against the privations visited upon some of its fellow crosses. The monuments at Charing Cross and Cheapside were both destroyed in a bout of Puritanical fervour (under an ordinance from the Parliamentary Committee for the Demolition of Monuments of Superstition and Idolatry) during the 1640s. In the early eighteenth century, the Eleanor Cross at St Albans, following years of neglect, was demolished. Later in the same century, the example at Waltham Cross was adorned with road signs. That the Eleanor Crosses have suffered the all too common traits of carelessness and wilful destruction is irrefutable. That the cross at Geddington still stands, both as a memorial to a Queen and as a tangible link to another age, is therefore a reason to celebration. That this monument, ‘one of the most sophisticated pieces of architecture…from the Middle Ages’ (Aslet, ibid) remains in near original condition is truly a reason to rejoice. References and Further Reading Alexander, J and Binski, P, Eds. (1987), Age of Chivalry: Art in Plantagenet England 1200-1400, Royal Academy Aslet, C (2005), Landmarks of Britain, Hodder and Stoughton

Click on the images to see each picture's full description

The screen

slams

Like a vision she

across the

As the radio plays

Roy Orbison singing for the lonely

that's me and I want you only

Don't turn me

again

I just can't

myself alone again

Don't

inside

Darling you know just what I'm here for

So you're

and you're

That maybe we ain't that young anymore

Show a little

there's

in the

You ain't a

but

you're alright

Oh and that's alright with me

You can

'neath your

And

your pain

Make

from your

Throw

in the

Waste your

in vain

For a

to rise from these

Well now I'm no hero

That's understood

All the redemption I can offer

Is beneath this dirty

With a chance to make it good somehow

what else can we do now?

Except roll down the

And let the

blow back your

Well the

busting open

These two

will take us anywhere

We got one last chance to make it real

To trade in these

on some

Climb in

Heaven's waiting on down the

Oh, oh come take my

We're

out tonight to case the promised land

Oh, oh

oh

Oh

out there like a

in the

I know it's late we can make it if we

Oh

sit tight

Well I got this guitar

And I learned how to make it talk

And my

out

If you're ready to take that long

From your front

to my front

The

open but the ride ain't free

And I know you're lonely

For words that I ain't spoke

Tonight we'll be free

All promises'll be broken

There were

in the

Of all the

you sent away

They haunt this dusty

road

In the

of burned out

They

your name at

in the

Your graduation

lies in rags at their

And in the lonely cool before dawn

You hear their engines

on

But when you get to the

they're gone on the wind

So

climb in

It's a

full of losers

I'm

out of here to win

Into the distance a

to the point of no turning

A

of fancy on a

field

alone my senses reeled

A

attraction is holding me fast

How can I escape this irresistible

Can't keep my

from the

and

just an earth bound misfit, I

is forming on the tips of my

Unheeded warnings

I though I'd thought of everything

No

to find my way

Unladened, empty and turned to

A soul in tension that's

to

Condition grounded but determined to try

Can't keep my

from the

and

just an earth bound misfit, I

Above the planet on a

and a

My grubby

a vapour trail in the empty air

Across the

I see my

Out of the corner of my

A

unthreatened by the morning

Could blow this soul

Right through the

of the

There's no sensation

to compare with this

animation, a state of bliss

Can't keep my mind from the

and

just an earth bound misfit, I

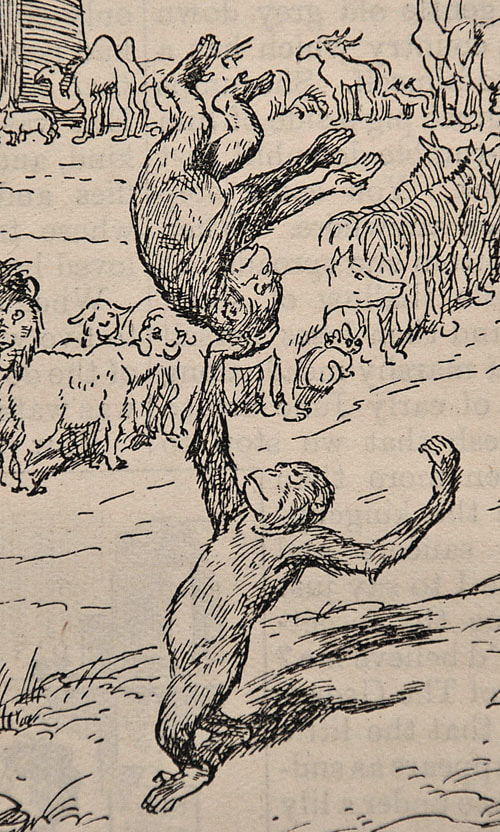

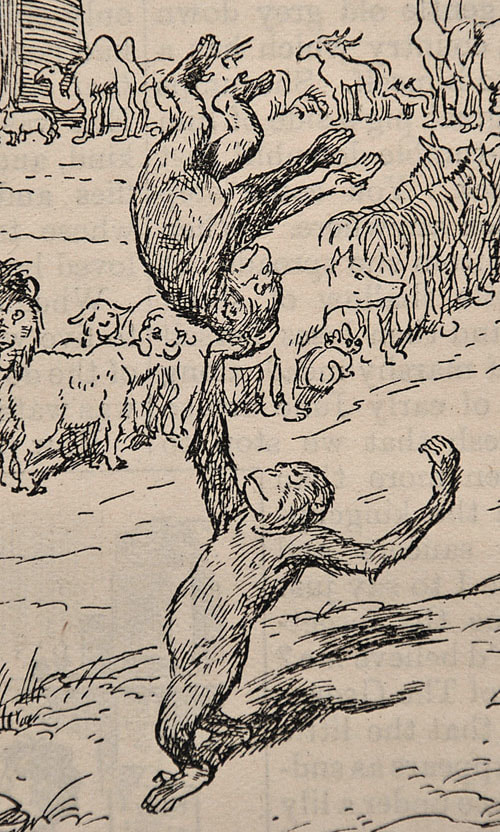

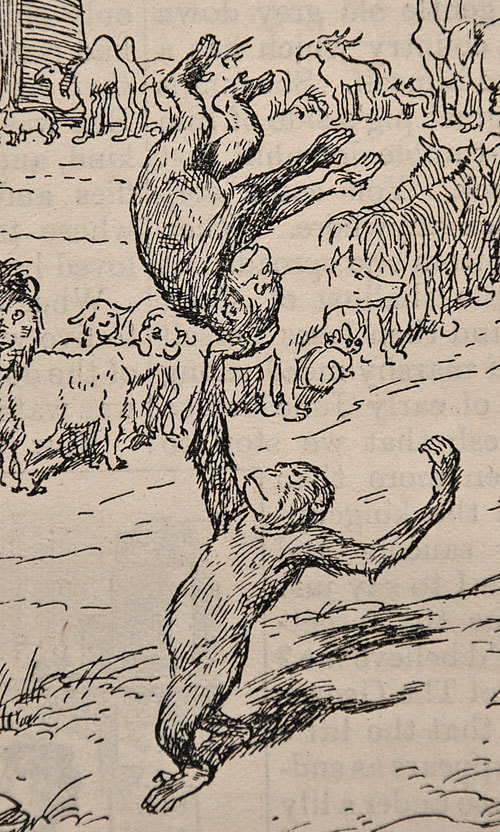

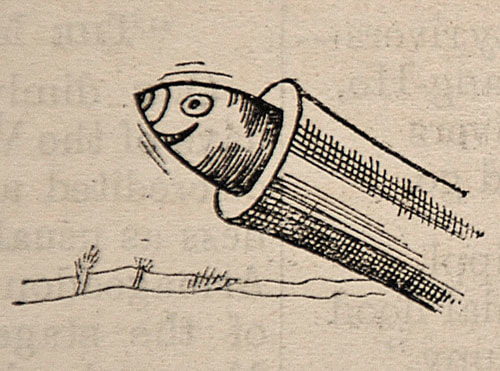

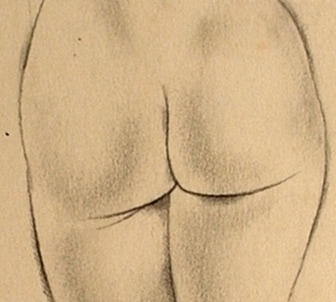

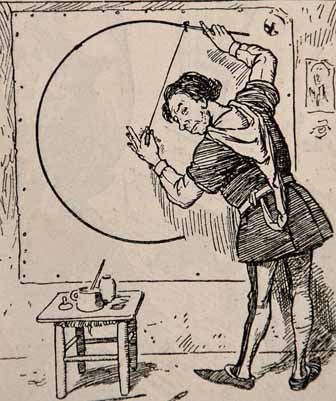

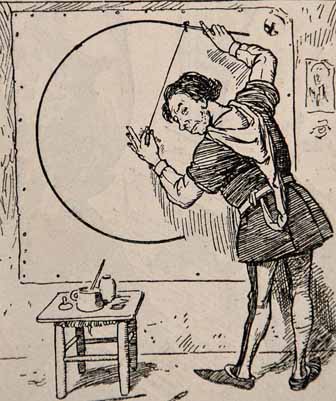

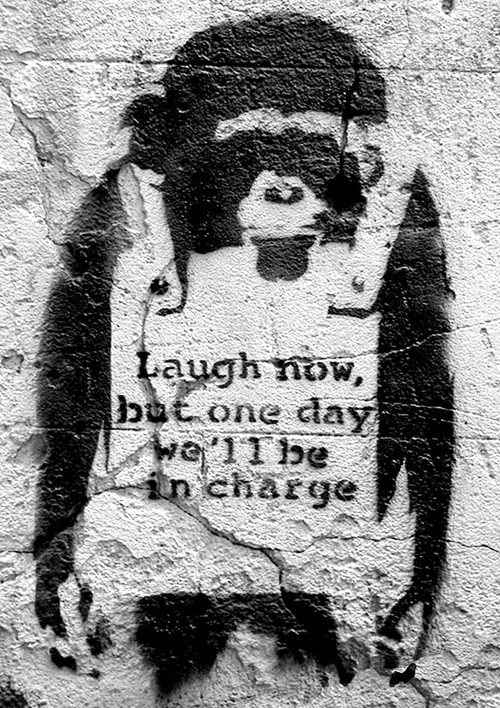

It is possible to view the history of art as a house with many levels. Fancifully, if we were to take a tour we might discover the prehistoric cave paintings at Altamira and Lascaux in the cellar before ascending to windowed rooms where we’ll find Egyptian art. Another staircase will take us to floors crammed with works from the Renaissance. As we climb further up the building we’ll pass through floors containing Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical art. The 19th century alone will contain numerous floors. By the time we reach the 20th century we’ll be many, many levels above the ground. Climbing on, we’ll reach the present day but we shouldn’t rest or pause too long. The tour won’t be over – this tour will never be over – for this is a house that will never be completed. Like all buildings, this arthouse has nooks and crevices hidden away that are rarely illuminated by the sun. In one of these nooks we might encounter paintings and drawings along similar lines to this: This charming work from our selection of drawings (appropriately titled Charmingly Finished; click here or on the drawing to see the full description) was sketched in 1823. The artist is unknown (it is initialled ‘W.T.C.’) but it provides a small insight into an overlooked subset of art history that first came to prominence in the 16th century. Known as singeries (from the French for ‘monkey tricks’), works depicting apes dressed as humans and acting in a human manner were first produced by Flemish artists; the idea was then taken up by painters and designers in France. Within in our house and its histories, the monkey has held numerous attributes. ‘Medieval and Renaissance man saw in the ape an image of his baser self. Thus it came to symbolize Lust, one of the seven deadly sins, idolatry and vice in general. In Christian art, with an apple in its mouth, it stood for the Fall of Man’ (Hall, 2001, p.10). A little further up the house, it was the artist who became most closely associated with the ape – both being known for their skill in imitation. This imitativeness was enshrined in the saying Ars simia Naturae – art is the ape of nature. In turn, this led to painters depicting ‘the artist as an ape, in the act of painting a portrait, generally of a female… This parody of man was extended to other human activities and apes were represented sitting at the meal table, playing cards or musical instruments, drinking, dancing and so on’ (Hall, 1989, p.22). The high point of anthropomorphised monkeys in art was during the Rococo period of the 18th century. Already a playful diversion in the arthouse, Rococo style was further enlivened by the introduction of monkeys in, for example, the work of Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), above. Although the vogue of Singeries largely died out in the nineteenth century, the monkey is still used (albeit without the anthropomorphism), for both parody and satire, in art today. Here on the top floor of the house we'll find monkeys in the work of Jeff Koons and far off in the distance we might find, beside a group of builders hastily constructing yet another staircase, something like this on the wall: And, as this is an imaginary house, we might find Banksy, spray can in hand, standing next to it.

References Hall, James (2001), Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art Hall, James (1989), Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art

You've left my

by the

Now is that

You've cleaned me out

you could say

Now is that

The

it gets

The more these

forget

That that is

You

you

Now is that, is that

A teasing

has

me out

Now is that, is that

The

it gets

The more my

frequent

Now that is

Beat me up with your

your walk out

Funny how you still find me

right here at

with a

and a

Now is that

that's making you

You've called my

I'm not so hot

Now is that

My assets

while yours have

Now is that, is that

It's the

That more or less survived

Now that is

Beat me up with your

your walk out

Funny how you still find me

right here at

with a

and a

Now is that

that's making you

You've made my

the

Now is that, is that

The

you

you

you cool down

The easier

is found

Now that is

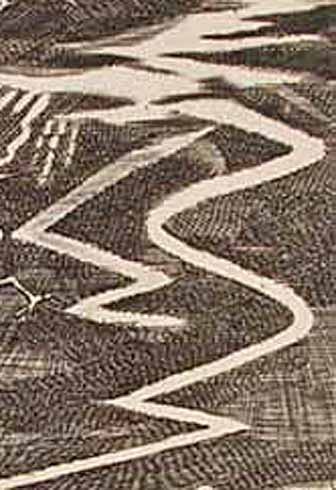

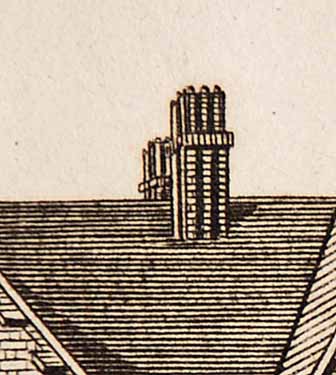

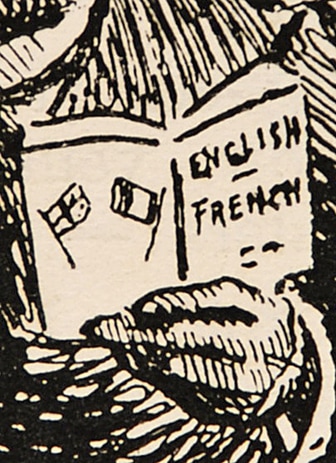

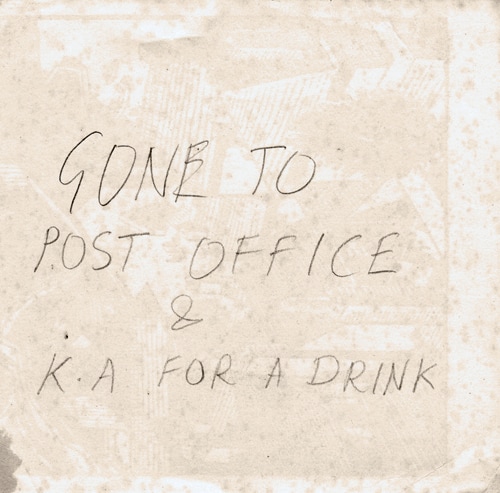

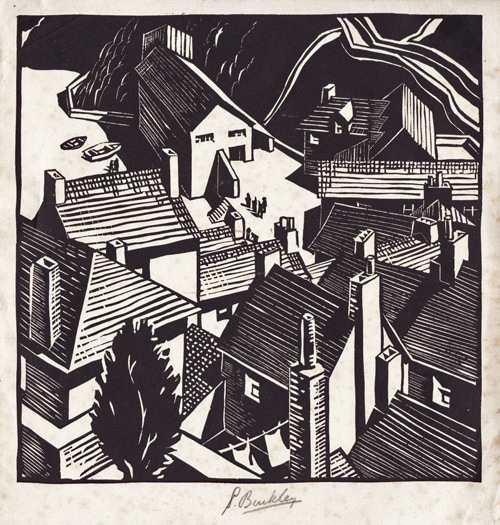

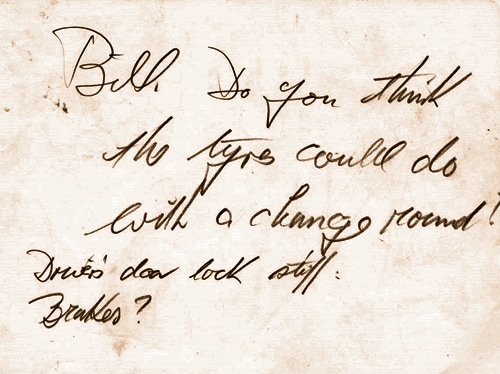

Today, we are blessed (or not) with a variety of convenient ways to communicate with each other. We can text, tweet and message and if the matter is urgent we can always fall back on ancient technology and make a phone call. In short, we can make contact and are contactable in return wherever we are at any time, instantly. It hasn’t always been this way. Back in the olden days (the 1960s or 1970s, say) if you wanted to communicate your whereabouts to the person you shared a house with, for example, the most expedient way would have been to leave them a note (look it up, kids). Here is just such a note and at first glance it appears to be nothing more than a mundane piece of domestic detritus. The author, as we can see, is off to the post office and the K.A. for a drink. We don’t need to bother Bletchley Park to conclude that in this instance, K.A. stands for Kings Arms. The note isn’t signed but I know who wrote it. I know because this is on the other side: The author was an artist called Sydney Buckley and the note was left for his sister with whom he shared a house at Cartmel in Cumbria. News of Buckley’s whereabouts was written on the reverse of this fine woodblock print titled Cornish Pattern which was designed and printed by Buckley perhaps in the 1940s or 1950s. The scene, typical of Cornwall, is of the rambling rooftops of a town edging on to a beach. In flavour and form it has the feel of Port Isaac, perhaps. It is showing some minor evidence of foxing and this may have existed when Buckley penned the note to his sister. Even so, it is a curious item to use to leave a note. Was there no other paper in the house? Buckley was a noted artist and printmaker (you can see two examples of his etched work on our website here and here) so it seems unlikely that the household was devoid of unused paper. This piece came from a larger collection of prints I bought about ten years ago, all by Buckley. There were ten or so copies of Cornish Pattern and I kept two. One is in mint condition with signature and title and the other is the copy illustrated above. Retained purely for its curiosity value, I was recently reminded of Buckley’s note when I acquired another small collection of artworks. These are all drawings and all by the same unknown hand (one of the many lost artists for whom the term ‘20th Century British School’ was invented). Here is one of the drawings: As we can see, it’s a competent, rapidly executed pencil sketch of a house. It is not fundamentally exciting as an image unless you happen to live in the depicted house, I suppose. Even so, the artist, for whatever reason, took the time and trouble to record the scene. The artist also used the reverse of the sheet for this: As the handwriting isn’t as clear as Buckley’s, here’s a transcript:

'Bill, do you think the tyres could do with a change round? Driver’s door lock stiff. Brakes?' Another note on the reverse of another artwork. It is possible with this example that the note preceded the drawing – at this remove there is no way of knowing for sure. But if the drawing came first, again, one has to ask why? Perhaps the artist dropped the car off at the garage and left the note on the car seat intending for Bill to read the message and then keep the note. This certainly didn’t happen – perhaps Bill didn’t turn the note over to see what was on the other side. Who knows? So many questions raised from two simple relics, each no more than forty of fifty years old, from a time before the age of instant communication. What, I wonder, did Buckley have to drink at the Kings Arms? And the enigmatic ‘Brakes?’ in the second message. Check the brakes? Fix the brakes? Sabotage the brakes? We’ll never know.

My life is a

You crawl through the

Slip across the

and into the reception room

You enter the place of endless persuasion

Like a knock on the

When there's

or more things to do

Who is that

You my companion

Run to the

on a burning

And it brings me relief

Pass through the

To find my intentions

round in a strange

state

I

There is no connection

A million points of

And a conversation I can't

Cast me off one day

To lose my inhibitions

Sit like a lap

on a matron's

Wear the nails on your

I woke up the

Stumbled in

The

went on and everybody screamed

The savage review

It left me

it warms my

to see that you can do it too

Total

Your

is so tender

Your

is like

on a

And it brings me relief

And it brings me relief

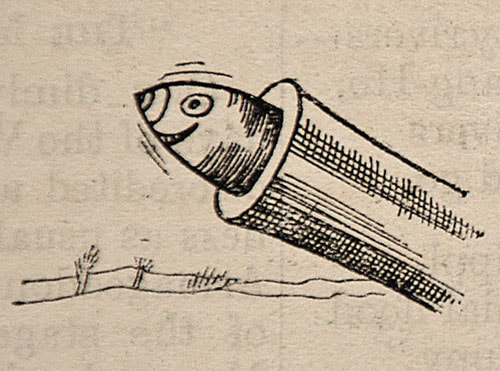

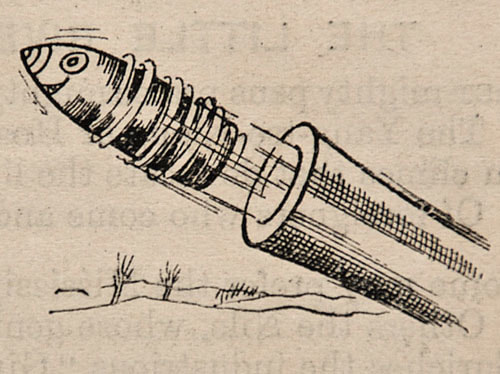

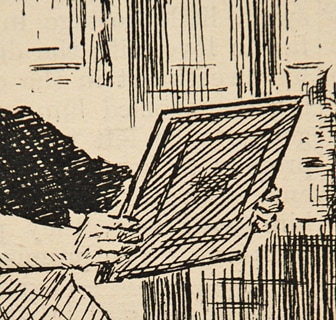

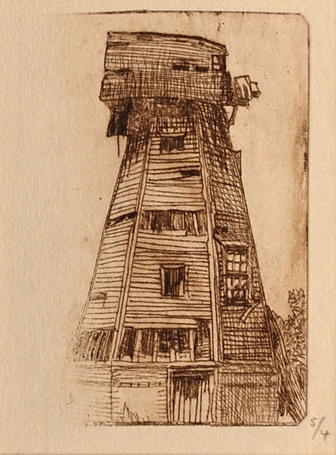

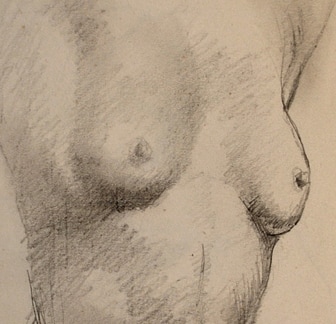

And it brings me relief The reputation of Karl Salsbury Wood (1888-1958) largely rests upon a remarkable series of paintings he produced between the late 1920s and his death in 1958. For almost thirty years Wood cycled around Britain in an attempt to visually record every existing windmill in the country. Wood’s plan was to publish a book titled The Twilight of the Mills containing his illustrations and written notes. In addition to being a talented (and clearly driven) painter, Wood was also a printmaker, as the small collection of etchings on our site illustrates (the full selection can be seen here). The subjects of the etchings reflect Wood’s interest in architecture and architectural details. Structures – castles, churches, inns and the ubiquitous windmills – are predominantly the focal point; the edges of the buildings straining up against the edges of the etching plate. A tree or two might act as the frame for a country church but it was unusual for Wood to record the bigger picture – the landscape the buildings exist within. The prints provide a useful insight into the way in which etchings are created. The etching process, though time-consuming, is relatively straightforward. A metal plate is coated in a layer of acid resistant wax, a design is then drawn on to the wax through to the metal plate and the plate is then immersed in acid. This bites away at the metal elements exposed by the artist’s design; the longer the plate is immersed the deeper the lines will be etched and the darker they will print. The etched image is constructed in stages (known as states), the various elements of the picture being worked on systematically until the finished image is arrived at. Windmill with Pigs (above) is clearly at a very early, rudimentary stage – just the outlines of the windmill and the pigs have been bitten. This print is numbered 1/1 which presumably means this is the first impression Wood took from the first state of the print. Here, Wood continues to develop a design in a third impression. As with Windmill with Pigs, major outlines were defined in the first impression, perhaps more detail was added to the windmill in the second and it is probable that the first elements of the sky were added in the third. States were completed, impressions were taken and the images continued to form and grow. Occasional mishaps clearly happened, too. The print above appears not to have been fully pressed as the left hand plate edge is entirely absent. Eventually, after many decisions regarding the location of the lines to be etched and the depth to which they should be bitten, a finished work of art was produced. Perhaps Wood made these etchings (based on the paintings and sketches he undertook on his journeys around the country) as a means of raising funds towards the publication of The Twilight of the Mills. Regrettably, as we discuss in the artist’s biographical notes here, the book was never published.

Click on the images to see each picture's description Round, like a in a spiral, like a within a Never ending or beginning on an ever-spinning Like a snowball down a or a carnival Like a carousel that's turning, running around the Like a whose hands are sweeping past the minutes of its And the world is like an silently in space Like the that you find in the of your mind Like a that you follow to a of its own Down a hollow to a where the sun has never shone Like a that keeps revolving in a half-forgotten dream Or the ripples from a someone tosses in a Like a whose hands are sweeping past the minutes of its And the world is like an silently in space Like the that you find in the of your mind that jingle in your pocket, words that jangle in your head Why did go so quickly? Was it something that you said? walk along a and leave their footprints in the Is the sound of distant just the fingers of your in a hallway or the fragment of a song Half-remembered names and but to whom do they belong? When you knew that it was over you were suddenly aware That the were turning to the colour of her A circle in a a within a Never ending or beginning on an ever-spinning As the images unwind like the that you find In the of your mind.

Johnny's in the Mixing up the I'm on the Thinking about the government The man in the out, laid off Says he's got a bad cough Wants to get it paid off Look out It's somethin' you did knows when But you're doin' it again You better down the alleyway Lookin' for a new friend A man in a coon-skin In a Wants eleven dollar bills You only got ten Maggie comes full of black soot Talkin' that the heat put in the bed but The tapped anyway Maggie says that many say They must in early May Orders from the Look out Don't matter what you did Walk on your Don't tie no Better stay away from those That carry around a fire Keep a clean Wash the plain clothes You don't need a weather man To know which way the Get sick, get well Hang around an inkwell Ring hard to tell If anything's gonna sell Try hard, get barred Get back, write braille Get jump bail Join the if you fail Look out You're gonna get hit But losers, cheaters Six-time users Hang around the Girl by the whirlpool is Lookin' for a new Don't follow leaders Watch the pawking metaws Ah, get born, keep warm romance, learn to Get dressed, get blessed Try to be a suckcess Please her, please him, buy gifts Don't steal, don't lift Twenty years of And they put you on the day shift Look out They keep it all hid Better jump down a Light yourself a Don't wear Try to avoid the scandals Don't wanna be a You better chew gum The don't work 'Cause the vandals took the

Click on the images to see each picture's description

I ain't got no

ain't got no

Ain't got no

ain't got no class

Ain't got no

ain't got no sweater

Ain't got no perfume

ain't got no

Ain't got no mind

Ain't got no

ain't got no culture

Ain't got no friends

ain't got no

Ain't got no

ain't got no name

Ain't got no

ain't got no

Ain't got no

And what have I got?

Why am I alive anyway?

Yeah, what have I got?

Nobody can take away

Got my

got my

Got my brains

Got my

Got my

got my

Got my

I got my

I got my tongue

Got my

Got my

got my

Got my

got my soul

Got my

I got my

I got my

got my

Got my

got my

Got my

got my

Got my liver

got my

I've got life

I've got my freedom

I've got the life.

The gremlins in Joe Dante’s 1984 film Gremlins aren’t actually gremlins – at least to begin with – they’re mogwais. Mogwais are happy little furry creatures and they’ll stay that way provided three simple rules are followed. When looking after mogwais, it is vital that:

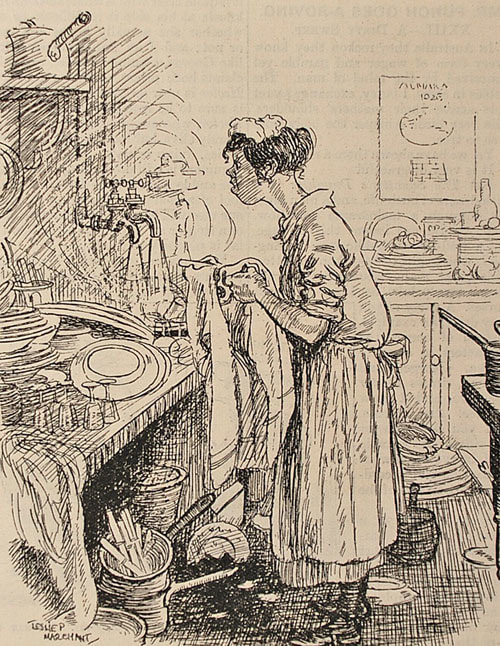

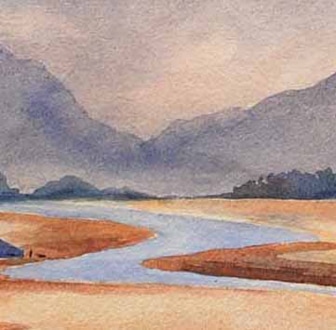

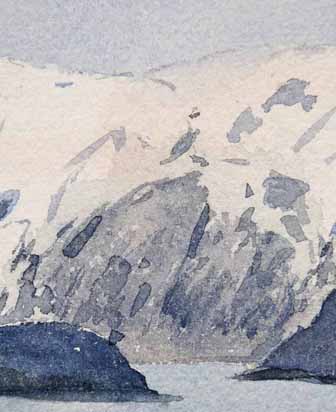

The regulations that govern the care of mogwais are simple and relatively straightforward (what ‘after midnight’ means is anyone’s guess) and they can be applied equally to the care of watercolours, drawings, etchings and engravings. In fact, the ‘mogwai rules’ are a useful primer when considering the mounting, framing and display of any work on paper. If you overly expose your watercolours to bright light (direct sunlight, for instance) they might react in a mogwailian fashion and fade away, over time, like a well-intentioned diet in the middle of January. Once-sharp colours can lose lustre and definition may blur. Naturally, we wouldn’t choose to get a paper-based artwork wet - that would ruin it. But moisture (due to an overly humid environment, for example) can be just as damaging. The picture on the right has been subjected to overly moist environment and is showing evidence of foxing as a result. And feeding? In addition to the moisture we unwittingly feed them we are also apt to expose our pictures to a varied diet of changing temperatures; hot, cold and all points in between. The very best place to display a work on paper is in a stable environment with a temperature of between 16°and 19°C and a relative humidity level between 45%-60% (source: Conservation Register, www.conservationregister.com). This is the ideal. It is also known as a museum. Museums have thermometers and hygrometers to measure ambient conditions and thermostats and humidifiers to maintain an optimum environment. Museum conditions are the gold standard but we, of course, don’t live in museums. We live in houses where we like to take steamy baths and showers; we might also, from time to time, have mist-emitting pans of vegetables bubbling away in our kitchens. In the winter, we like to have the central heating on in the morning, turn it off when we go to work and turn it back on again in the evening. Thus we live in occasionally humid environments with large variances in temperature. In terms of paper-based art, our homes are not stable environments. Does this mean we can’t own watercolours? No, of course not. For thousands of years, we humans have sought to decorate and embellish the spaces we choose to occupy – it is an innate human instinct (you can satisfy your own innate human instinct by visiting our ‘Watercolours’ section here). Happily, there are tools at our disposal that help us limit any potential risks to art – namely knowledge and choice.  We now know more about how to conserve and care for the works we own. The picture on the left shows a print that was mounted in the late 19th or early 20th century. The mount boards from that period were made of acidic wood pulp and we can clearly see how this has ‘burnt’ the paper. Today, acid-free mount boards are readily available (The Saturday Gallery only uses conservation-grade board for the works we mount in-house) and additional protection is provided once works are framed and appropriately sealed to the reverse. In terms of choice, we can decide where best to hang a particular work. For watercolours, drawing and prints, opposite a south-facing window may not be such a good idea. Similarly, you might want to reconsider if you decide that the best place for a fine watercolour is above the bath tub.

Thanks to the work of conservators we know what harms works on paper and we have a better understanding of what we can do to reduce the potential risks to them. So next time you are deciding how to mount and frame a piece or considering where to hang it, remember it’s not just a watercolour or a drawing or a print – it’s also a mogwai. And you wouldn’t want it to turn into a gremlin. Next time: Oil Paintings and Ewoks: Just Good Friends or Something More Serious? |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed