|

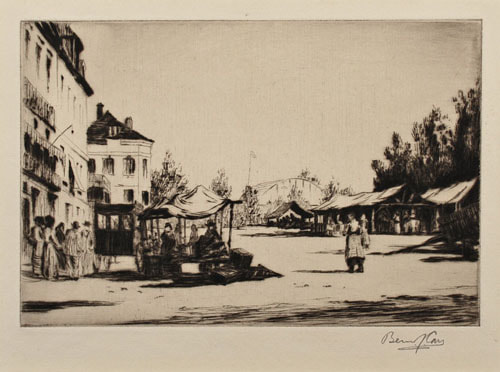

Etching as an artistic medium can be dated back to the beginning of the sixteenth century. The earliest dated etching is Girl Bathing Her Feet by Urs Graf of 1513. Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Albrecht Altdorfer (1480-1538) were early masters of the new technique which flourished on the continent as the century progressed. During the following century, Rembrandt (1606-1669) embraced the relative freedom of expression that the technique offered to produce over 300 original etchings. Thereafter, however, ‘for the century and a half that followed the death of Rembrandt the art of original etching was little practiced and less understood’ (Hind, p.312). During the early nineteenth century etching held a minor position in the arts in Britain. Considered something of a ‘lost’ technique, it was little utilised until the formation of the Old Etching Club in London in 1838. Members of the Club, and the Junior Etching Club that developed from the original group, were principally concerned with producing etchings to illustrate works of literature in an effort to subsidise their primary pursuit of painting. For much of the nineteenth century etching was considered a minor element of the artistic canon; indeed, the Royal Academy gave greater prominence to engraved reproductions of paintings than it did to original prints. This dismissive attitude was to change due primarily to the work of Francis Seymour Haden (1818-1910) and his brother in law James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). These two men, through a combination of example and promotion, provided the platform for a renewed interest in etching. In the mid-1850s, Whistler spent three years in France where he had been introduced to the work of Charles Meryon (1821-1868), Félix Bracquemond (1833-1914) and Charles Jacque (1813-1894), the leading French etchers of the time. In 1858 Whistler moved to London where, influenced by the work he had seen in Paris, he began a series of etchings of scenes along the River Thames. By the late 1870s, the Old Etching Club had largely ceased to function as anything other than a social group. Haden, a surgeon and talented etcher, proposed the formation of a new society dedicated to promoting etching as an important medium in its own right. The first meeting of the Society of Painter-Etchers was held in 1880 with Haden its President. He gave the group its original motto: Ne Desilies Imitator – ‘Do not stoop to be a copyist.’ In this phrase lay Haden’s central aim – that printmakers should produce original works and, by extension, the art of etching should come to be viewed as a valid and important artistic medium. Eight years after its formation the Society was granted a Royal Charter and six years later, in 1894, Haden was knighted for his service to the arts. The influence Haden exerted over the Society was immense. He promoted the idea that an artist could convey as much with empty space as he or she could through the use of a multitude of unnecessary (as Haden saw it) bitten lines. He also believed that each artist should, where possible, draw onto pre-prepared plates, directly from nature. To ensure that all aspects of the process could be overseen by the artist, Haden further suggested that etchers should master the techniques of the press to enable them to print and proof their own work. Demand for original etchings grew steadily through the later years of the nineteenth century. This growing interest was encouraged by the efforts of Phillip Gilbert Hamerton (1834-1894), ‘the chief publicist for the British [etching] revival’ (Lang and Lang, p.42). Hamerton, himself a keen etcher, believed that the biggest obstacle to the acceptance of etching as a valid art form was a largely ignorant public. He endeavoured to rectify this through the publication of Etching and Etchers (1868) in which he lauded the efforts of Whistler and Haden (‘Here is a book written to increase the public interest in an art we [Haden and Hamerton] both love’, was the rallying first line of the book’s dedication to Haden). Furthermore, Hamerton argued against the prevailing view that the technique was a purely illustrative medium. Published at a guinea and a half and much to Hamerton’s surprise, the book rapidly sold out. The success of Etching and Etchers confirmed Hamerton’s belief that an educated public could lead to an informed and enthusiastic market. Hamerton’s subsequent publications (The Portfolio, The Etcher and English Etchings published between 1879 and 1891) continued to supply an ever more interested public with information about works by the growing spectrum of artists working in the medium. Throughout the first decade of the twentieth century as the number of practitioners increased so the demand for original etchings also grew. In 1911 The Print Collector’s Quarterly was launched ‘as a response and a stimulant to the growing demand’ (Lang and Lang, p.51). The market for original etchings increased rapidly, reaching its zenith in the decade immediately after the First World War. Print auctions at Sotheby’s increased from six to twenty four sales a year during the second half of the 1920s and the prices for individual works similarly escalated. Muirhead Bone’s Ayr Prison, originally published in 1905 for £2.2.6, sold for £365 in 1929; David Young Cameron’s Five Sisters, York Minster set the record price for a print by a living artist in 1928 when a collector paid £660 for a copy.

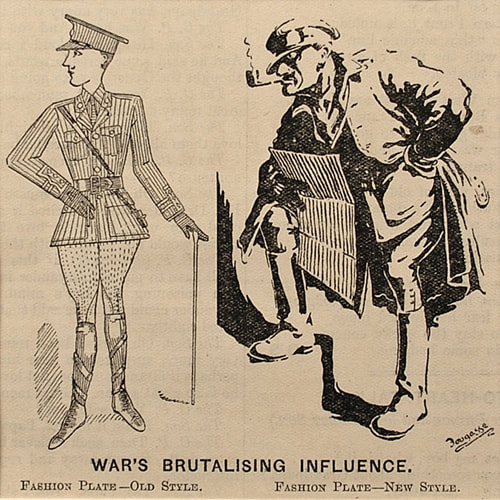

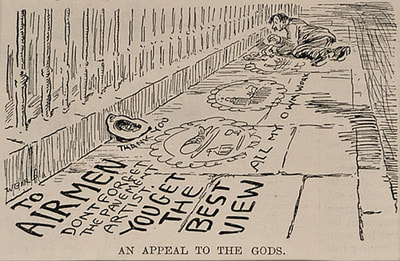

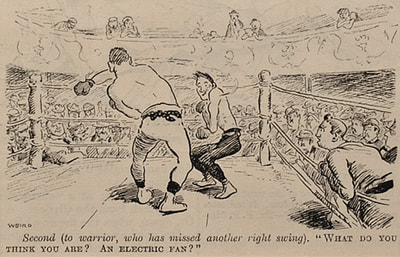

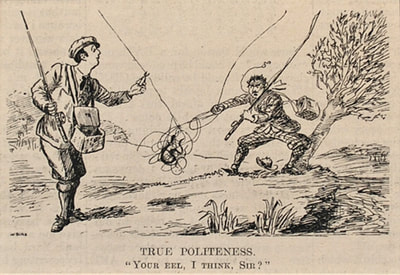

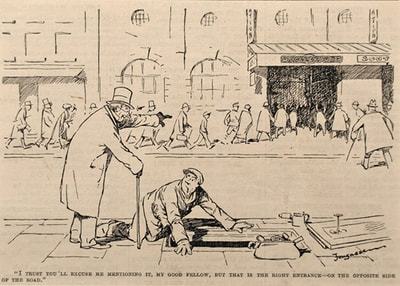

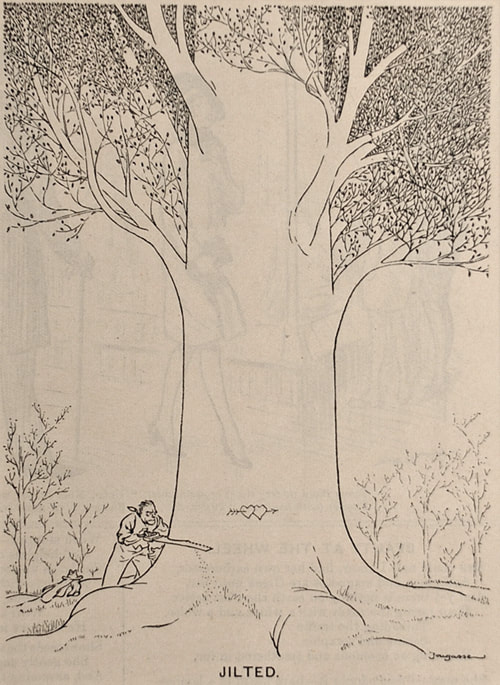

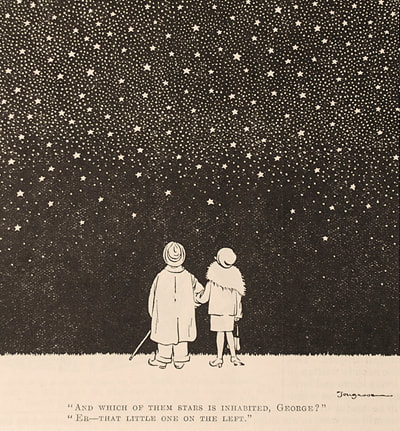

Soon after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 the market for original prints collapsed. The pioneering work of Whistler and Haden coupled with Hamerton’s promotional zeal produced a period of unmatched popularity and recognition for a previously overlooked and neglected technique. Due to the diminishing market, the production of original etchings slowed and has never returned to the levels of the 1920s. The craze for original etchings may now be a century old but the medium endures as does the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers. Today it is called the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers and it continues to hold exhibitions showcasing artists working in this most expressive and striking medium. This essay is a modified and abridged version of the author’s introduction to the catalogue for the exhibition Whistler, Haden and the Rise of the Painter-Etcher, held at the Hatton Gallery, University of Newcastle in 2001. We discuss the etching technique in more detail in our short article about the work of Karl Salsbury Wood here. More information about the work and history of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers can be found on their website. Sources and further reading Farr, D (1978), English Art 1870-1940, Oxford University Press Furst, H (1931), Original Etching and Engraving, An Appreciation, T. Nelson and Sons Garton, R (1992), British Printmakers 1855-1955, Garton and Co Gray, B (1937), The English Print, Adam and Charles Black Heard, A (2001), Whistler, Haden and the Rise of the Painter-Etcher, University of Newcastle Hind, A M (1923), A History of Engraving and Etching from the 15th Century to the Year 1814, Constable and Company Lang, G E and Lang K (1990), Etched in Memory, The University of North Carolina Press Laver, J (1929), A History of British and American Etching, Ernest Benn Ltd Rowland, S (1940), The Decline of Etching in Apollo, July 1940 During the First World War, Kenneth Bird was hospitalised following an injury to his spine sustained at Gallipoli in 1915. Prior to the war, Bird had been an instructor with the Artists’ Rifles and had worked at the Rosyth naval base. ‘Horribly wounded… [he] realised he would have to find something to do which would not overtax him physically.’ (Anderson, p.156). Having earlier attended evening classes in art at Regent Street Polytechnic, that ‘something’ was cartoons and illustrations which Bird submitted to numerous publications. His first cartoon for Punch, below, was published in 1916. When War’s Brutalising Influence was published there was another artist submitting to Punch who signed his work ‘W. Bird’. For this reason, Kenneth Bird adopted the name ‘Fougasse’, a small improvised land mine of the type he would have encountered during the war, for his cartoons, illustrations and designs. The other cartoonist wasn’t actually a Bird at all. ‘W. Bird’ was Jack Butler Yeats, author, Olympic medallist and Ireland’s most influential artist of the twentieth century. As can be seen in the images above, Yeats’ submissions to Punch are characterised by a free-flowing, loosely handled style. This approach, so expressively forceful, vibrant and modern when employed by Yeats in colour on canvas, looked, to a contemporary audience, hasty, sketchy and somewhat amateurish in black and white. As Price (p.209) related, ‘Townsend and Seaman [Punch’s Art Editor and Editor at the time] continued to print… Bird, though many readers must have brought pressure on them, attacking Bird’s drawings as not representing reality.’ In fact, Bird’s drawings did represent reality – they just didn’t represent it in the manner to which Punch readers had become accustomed, as the two cartoons below (Yeats left; G D Armour, a contemporary Punch cartoonist, right) illustrate. Leaving aside the merits or demerits of the humour, Yeats’ cartoons are published sketches whereas Fougasse’s are coherent and fully formed designs. They possess an intrinsic strength of line coupled with the parsimony of a dedicated minimalist to show just enough to carry the joke or make the point. Whether it was two fellows negatively silhouetted against a hatched hedge or two others before an Underground station, Fougasse clearly understood that, when working in monochrome, sparseness can be strength. They were modern, too, and would have seemed so to contemporary eyes. There is a timeless element to Fougasse’s more successful cartoons. If you’d have found Jilted, above, funny in 1926 there is no reason not to find it funny today. It doesn’t require an understanding of time and place for the laugh; all the viewer needs is an emotional connection to the subject. Such a work is relevant today in part because it deals with a universally understood situation and also because of the strength of the cartoon’s design. This design ethic runs through Fougasse’s work – he instinctively knew where to place a line and, crucially, when to leave a line out. He also understood the impact bold contrast could produce. In 1937, Fougasse was made Art Editor of Punch and continued to publish his own drawings. Over time, his technique simplified further, becoming even more stripped back and to the point. His mature style was employed to great effect during the Second World War in the ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ propaganda posters he designed for the Ministry of Information. In 1949, Fougasse was made Punch Editor, the only cartoonist in the history of the magazine to hold the position.

Yeats, too, continued to submit ‘W. Bird’ cartoons to Punch until 1941. Away from his published drawings, his individual, expressionist paintings ‘helped articulate a modern Ireland of the twentieth century’ (Brennan, 2007). Additionally, he published novels, wrote plays and designed sets for the Abbey Theatre, Dublin. In 1924, following the establishment of the Irish Free State, Yeats won the country’s first medal at the modern Olympic Games. The discipline was Painting and Yeats was awarded the silver medal for a work titled The Liffey Swim. Painting was one of the Arts categories which featured at Olympic competitions from 1912 to 1948. Our full selection of Punch cartoons can be seen here. Our biographies of Bird, Yeats and other Punch cartoonists can be seen here. Sources and further reading Anderson A (1982), The Man Who Was H M Bateman, Webb and Bower Brennan S (2007), A speech delivered at the National Gallery of Ireland Bryant M and Heneage S (1994), Dictionary of British Cartoonists and Caricaturists 1730-1980, Scolar Press Price R G G ((1957), A History of Punch, Collins In 1290, Eleanor, Edward I’s Queen died at Harby near Lincoln from a fever. The King, heartbroken and in mourning accompanied Eleanor’s body (minus her internal organs which were interred at Lincoln) on its slow procession to London for burial at Westminster Abbey. In commemoration of his late Queen, Edward had twelve memorial crosses erected at the points where the body had rested each night on its journey south. The cortege’s progress had been slow, being ‘dictated by the royal houses and monasteries where the king could spend the night’ (Aslet, p.323). The resulting twelve crosses were the work of different designers and masons and were not uniform in style or size. It is safe to assume that the grandest of the twelve were at Cheapside and Charing Cross in London if only because the accounts from the time indicate that these were the most expensive constructions (Alexander and Binski, p.362). Some speculation is necessary when discussing the Eleanor Crosses because, of the twelve that were built in the 1290s, only three – at Waltham Cross, Hardingstone and Geddington (below) survive today. The monument now outside Charing Cross station, incidentally, is Victorian; it is not a replica of the thirteenth century cross, nor is it at the site of the original. In 1290, Geddington, home to royal hunting lodge, was the third halt, after Grantham and Stamford, on the journey to London. Today, this fine memorial looks just as it did when this engraving was published in 1805 (you can see the full item description here). Moreover, apart from some natural weathering, the cross looks the same as it did when it was built around 725 years ago.

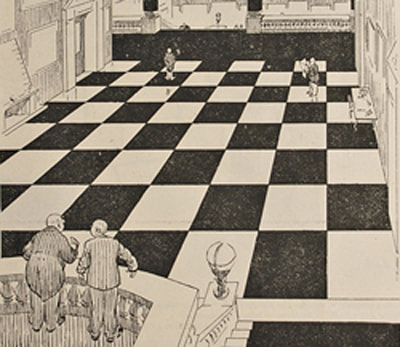

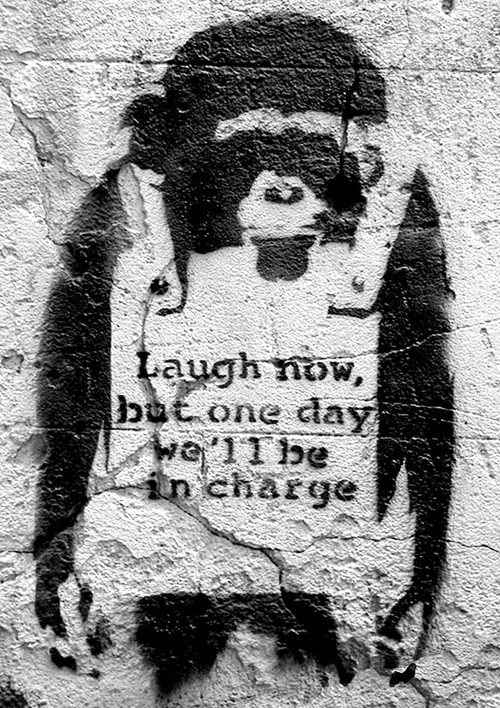

Geddington’s longevity and relative intactness is all the more impressive when viewed against the privations visited upon some of its fellow crosses. The monuments at Charing Cross and Cheapside were both destroyed in a bout of Puritanical fervour (under an ordinance from the Parliamentary Committee for the Demolition of Monuments of Superstition and Idolatry) during the 1640s. In the early eighteenth century, the Eleanor Cross at St Albans, following years of neglect, was demolished. Later in the same century, the example at Waltham Cross was adorned with road signs. That the Eleanor Crosses have suffered the all too common traits of carelessness and wilful destruction is irrefutable. That the cross at Geddington still stands, both as a memorial to a Queen and as a tangible link to another age, is therefore a reason to celebration. That this monument, ‘one of the most sophisticated pieces of architecture…from the Middle Ages’ (Aslet, ibid) remains in near original condition is truly a reason to rejoice. References and Further Reading Alexander, J and Binski, P, Eds. (1987), Age of Chivalry: Art in Plantagenet England 1200-1400, Royal Academy Aslet, C (2005), Landmarks of Britain, Hodder and Stoughton It is possible to view the history of art as a house with many levels. Fancifully, if we were to take a tour we might discover the prehistoric cave paintings at Altamira and Lascaux in the cellar before ascending to windowed rooms where we’ll find Egyptian art. Another staircase will take us to floors crammed with works from the Renaissance. As we climb further up the building we’ll pass through floors containing Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical art. The 19th century alone will contain numerous floors. By the time we reach the 20th century we’ll be many, many levels above the ground. Climbing on, we’ll reach the present day but we shouldn’t rest or pause too long. The tour won’t be over – this tour will never be over – for this is a house that will never be completed. Like all buildings, this arthouse has nooks and crevices hidden away that are rarely illuminated by the sun. In one of these nooks we might encounter paintings and drawings along similar lines to this: This charming work from our selection of drawings (appropriately titled Charmingly Finished; click here or on the drawing to see the full description) was sketched in 1823. The artist is unknown (it is initialled ‘W.T.C.’) but it provides a small insight into an overlooked subset of art history that first came to prominence in the 16th century. Known as singeries (from the French for ‘monkey tricks’), works depicting apes dressed as humans and acting in a human manner were first produced by Flemish artists; the idea was then taken up by painters and designers in France. Within in our house and its histories, the monkey has held numerous attributes. ‘Medieval and Renaissance man saw in the ape an image of his baser self. Thus it came to symbolize Lust, one of the seven deadly sins, idolatry and vice in general. In Christian art, with an apple in its mouth, it stood for the Fall of Man’ (Hall, 2001, p.10). A little further up the house, it was the artist who became most closely associated with the ape – both being known for their skill in imitation. This imitativeness was enshrined in the saying Ars simia Naturae – art is the ape of nature. In turn, this led to painters depicting ‘the artist as an ape, in the act of painting a portrait, generally of a female… This parody of man was extended to other human activities and apes were represented sitting at the meal table, playing cards or musical instruments, drinking, dancing and so on’ (Hall, 1989, p.22). The high point of anthropomorphised monkeys in art was during the Rococo period of the 18th century. Already a playful diversion in the arthouse, Rococo style was further enlivened by the introduction of monkeys in, for example, the work of Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), above. Although the vogue of Singeries largely died out in the nineteenth century, the monkey is still used (albeit without the anthropomorphism), for both parody and satire, in art today. Here on the top floor of the house we'll find monkeys in the work of Jeff Koons and far off in the distance we might find, beside a group of builders hastily constructing yet another staircase, something like this on the wall: And, as this is an imaginary house, we might find Banksy, spray can in hand, standing next to it.

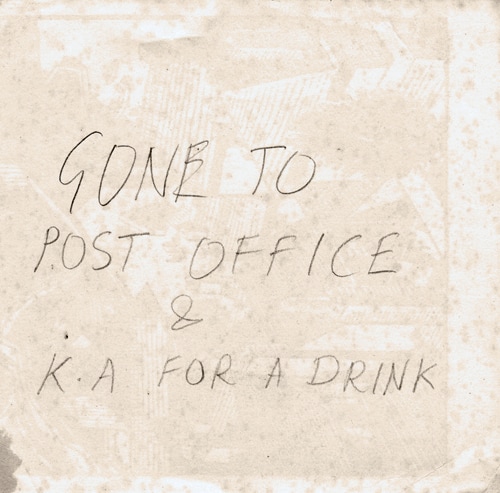

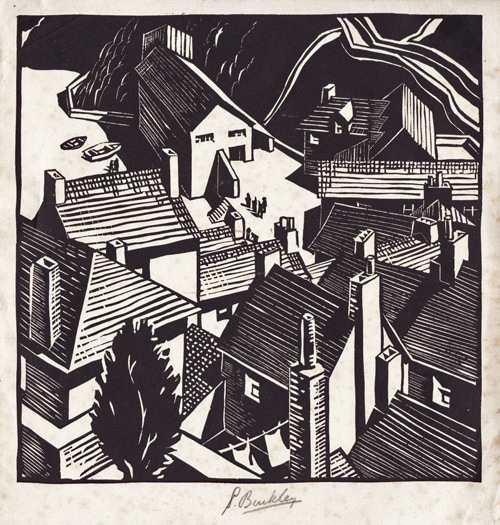

References Hall, James (2001), Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art Hall, James (1989), Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art Today, we are blessed (or not) with a variety of convenient ways to communicate with each other. We can text, tweet and message and if the matter is urgent we can always fall back on ancient technology and make a phone call. In short, we can make contact and are contactable in return wherever we are at any time, instantly. It hasn’t always been this way. Back in the olden days (the 1960s or 1970s, say) if you wanted to communicate your whereabouts to the person you shared a house with, for example, the most expedient way would have been to leave them a note (look it up, kids). Here is just such a note and at first glance it appears to be nothing more than a mundane piece of domestic detritus. The author, as we can see, is off to the post office and the K.A. for a drink. We don’t need to bother Bletchley Park to conclude that in this instance, K.A. stands for Kings Arms. The note isn’t signed but I know who wrote it. I know because this is on the other side: The author was an artist called Sydney Buckley and the note was left for his sister with whom he shared a house at Cartmel in Cumbria. News of Buckley’s whereabouts was written on the reverse of this fine woodblock print titled Cornish Pattern which was designed and printed by Buckley perhaps in the 1940s or 1950s. The scene, typical of Cornwall, is of the rambling rooftops of a town edging on to a beach. In flavour and form it has the feel of Port Isaac, perhaps. It is showing some minor evidence of foxing and this may have existed when Buckley penned the note to his sister. Even so, it is a curious item to use to leave a note. Was there no other paper in the house? Buckley was a noted artist and printmaker (you can see two examples of his etched work on our website here and here) so it seems unlikely that the household was devoid of unused paper. This piece came from a larger collection of prints I bought about ten years ago, all by Buckley. There were ten or so copies of Cornish Pattern and I kept two. One is in mint condition with signature and title and the other is the copy illustrated above. Retained purely for its curiosity value, I was recently reminded of Buckley’s note when I acquired another small collection of artworks. These are all drawings and all by the same unknown hand (one of the many lost artists for whom the term ‘20th Century British School’ was invented). Here is one of the drawings: As we can see, it’s a competent, rapidly executed pencil sketch of a house. It is not fundamentally exciting as an image unless you happen to live in the depicted house, I suppose. Even so, the artist, for whatever reason, took the time and trouble to record the scene. The artist also used the reverse of the sheet for this: As the handwriting isn’t as clear as Buckley’s, here’s a transcript:

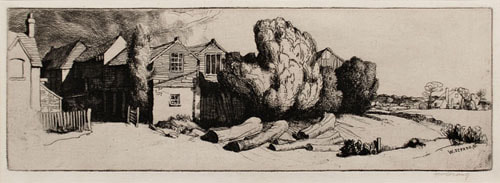

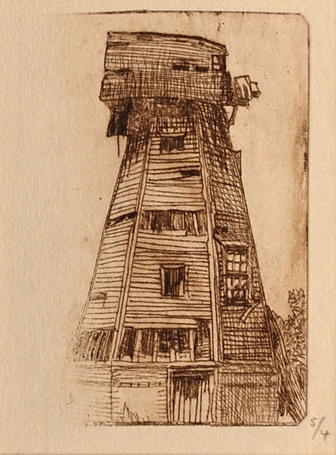

'Bill, do you think the tyres could do with a change round? Driver’s door lock stiff. Brakes?' Another note on the reverse of another artwork. It is possible with this example that the note preceded the drawing – at this remove there is no way of knowing for sure. But if the drawing came first, again, one has to ask why? Perhaps the artist dropped the car off at the garage and left the note on the car seat intending for Bill to read the message and then keep the note. This certainly didn’t happen – perhaps Bill didn’t turn the note over to see what was on the other side. Who knows? So many questions raised from two simple relics, each no more than forty of fifty years old, from a time before the age of instant communication. What, I wonder, did Buckley have to drink at the Kings Arms? And the enigmatic ‘Brakes?’ in the second message. Check the brakes? Fix the brakes? Sabotage the brakes? We’ll never know. The reputation of Karl Salsbury Wood (1888-1958) largely rests upon a remarkable series of paintings he produced between the late 1920s and his death in 1958. For almost thirty years Wood cycled around Britain in an attempt to visually record every existing windmill in the country. Wood’s plan was to publish a book titled The Twilight of the Mills containing his illustrations and written notes. In addition to being a talented (and clearly driven) painter, Wood was also a printmaker, as the small collection of etchings on our site illustrates (the full selection can be seen here). The subjects of the etchings reflect Wood’s interest in architecture and architectural details. Structures – castles, churches, inns and the ubiquitous windmills – are predominantly the focal point; the edges of the buildings straining up against the edges of the etching plate. A tree or two might act as the frame for a country church but it was unusual for Wood to record the bigger picture – the landscape the buildings exist within. The prints provide a useful insight into the way in which etchings are created. The etching process, though time-consuming, is relatively straightforward. A metal plate is coated in a layer of acid resistant wax, a design is then drawn on to the wax through to the metal plate and the plate is then immersed in acid. This bites away at the metal elements exposed by the artist’s design; the longer the plate is immersed the deeper the lines will be etched and the darker they will print. The etched image is constructed in stages (known as states), the various elements of the picture being worked on systematically until the finished image is arrived at. Windmill with Pigs (above) is clearly at a very early, rudimentary stage – just the outlines of the windmill and the pigs have been bitten. This print is numbered 1/1 which presumably means this is the first impression Wood took from the first state of the print. Here, Wood continues to develop a design in a third impression. As with Windmill with Pigs, major outlines were defined in the first impression, perhaps more detail was added to the windmill in the second and it is probable that the first elements of the sky were added in the third. States were completed, impressions were taken and the images continued to form and grow. Occasional mishaps clearly happened, too. The print above appears not to have been fully pressed as the left hand plate edge is entirely absent. Eventually, after many decisions regarding the location of the lines to be etched and the depth to which they should be bitten, a finished work of art was produced. Perhaps Wood made these etchings (based on the paintings and sketches he undertook on his journeys around the country) as a means of raising funds towards the publication of The Twilight of the Mills. Regrettably, as we discuss in the artist’s biographical notes here, the book was never published.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed