|

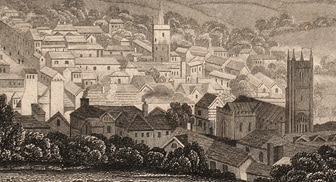

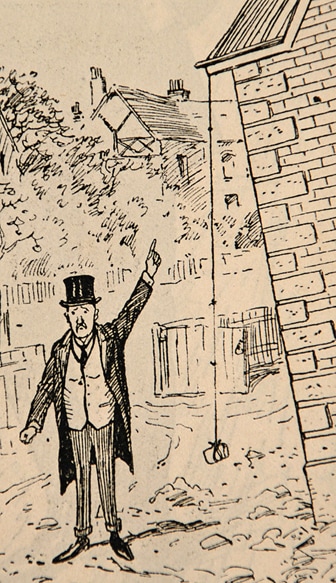

In 1290, Eleanor, Edward I’s Queen died at Harby near Lincoln from a fever. The King, heartbroken and in mourning accompanied Eleanor’s body (minus her internal organs which were interred at Lincoln) on its slow procession to London for burial at Westminster Abbey. In commemoration of his late Queen, Edward had twelve memorial crosses erected at the points where the body had rested each night on its journey south. The cortege’s progress had been slow, being ‘dictated by the royal houses and monasteries where the king could spend the night’ (Aslet, p.323). The resulting twelve crosses were the work of different designers and masons and were not uniform in style or size. It is safe to assume that the grandest of the twelve were at Cheapside and Charing Cross in London if only because the accounts from the time indicate that these were the most expensive constructions (Alexander and Binski, p.362). Some speculation is necessary when discussing the Eleanor Crosses because, of the twelve that were built in the 1290s, only three – at Waltham Cross, Hardingstone and Geddington (below) survive today. The monument now outside Charing Cross station, incidentally, is Victorian; it is not a replica of the thirteenth century cross, nor is it at the site of the original. In 1290, Geddington, home to royal hunting lodge, was the third halt, after Grantham and Stamford, on the journey to London. Today, this fine memorial looks just as it did when this engraving was published in 1805 (you can see the full item description here). Moreover, apart from some natural weathering, the cross looks the same as it did when it was built around 725 years ago.

Geddington’s longevity and relative intactness is all the more impressive when viewed against the privations visited upon some of its fellow crosses. The monuments at Charing Cross and Cheapside were both destroyed in a bout of Puritanical fervour (under an ordinance from the Parliamentary Committee for the Demolition of Monuments of Superstition and Idolatry) during the 1640s. In the early eighteenth century, the Eleanor Cross at St Albans, following years of neglect, was demolished. Later in the same century, the example at Waltham Cross was adorned with road signs. That the Eleanor Crosses have suffered the all too common traits of carelessness and wilful destruction is irrefutable. That the cross at Geddington still stands, both as a memorial to a Queen and as a tangible link to another age, is therefore a reason to celebration. That this monument, ‘one of the most sophisticated pieces of architecture…from the Middle Ages’ (Aslet, ibid) remains in near original condition is truly a reason to rejoice. References and Further Reading Alexander, J and Binski, P, Eds. (1987), Age of Chivalry: Art in Plantagenet England 1200-1400, Royal Academy Aslet, C (2005), Landmarks of Britain, Hodder and Stoughton

Click on the images to see each picture's full description

The screen

slams

Like a vision she

across the

As the radio plays

Roy Orbison singing for the lonely

that's me and I want you only

Don't turn me

again

I just can't

myself alone again

Don't

inside

Darling you know just what I'm here for

So you're

and you're

That maybe we ain't that young anymore

Show a little

there's

in the

You ain't a

but

you're alright

Oh and that's alright with me

You can

'neath your

And

your pain

Make

from your

Throw

in the

Waste your

in vain

For a

to rise from these

Well now I'm no hero

That's understood

All the redemption I can offer

Is beneath this dirty

With a chance to make it good somehow

what else can we do now?

Except roll down the

And let the

blow back your

Well the

busting open

These two

will take us anywhere

We got one last chance to make it real

To trade in these

on some

Climb in

Heaven's waiting on down the

Oh, oh come take my

We're

out tonight to case the promised land

Oh, oh

oh

Oh

out there like a

in the

I know it's late we can make it if we

Oh

sit tight

Well I got this guitar

And I learned how to make it talk

And my

out

If you're ready to take that long

From your front

to my front

The

open but the ride ain't free

And I know you're lonely

For words that I ain't spoke

Tonight we'll be free

All promises'll be broken

There were

in the

Of all the

you sent away

They haunt this dusty

road

In the

of burned out

They

your name at

in the

Your graduation

lies in rags at their

And in the lonely cool before dawn

You hear their engines

on

But when you get to the

they're gone on the wind

So

climb in

It's a

full of losers

I'm

out of here to win

Into the distance a

to the point of no turning

A

of fancy on a

field

alone my senses reeled

A

attraction is holding me fast

How can I escape this irresistible

Can't keep my

from the

and

just an earth bound misfit, I

is forming on the tips of my

Unheeded warnings

I though I'd thought of everything

No

to find my way

Unladened, empty and turned to

A soul in tension that's

to

Condition grounded but determined to try

Can't keep my

from the

and

just an earth bound misfit, I

Above the planet on a

and a

My grubby

a vapour trail in the empty air

Across the

I see my

Out of the corner of my

A

unthreatened by the morning

Could blow this soul

Right through the

of the

There's no sensation

to compare with this

animation, a state of bliss

Can't keep my mind from the

and

just an earth bound misfit, I

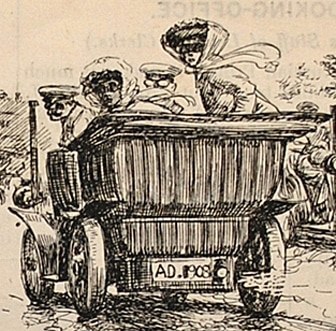

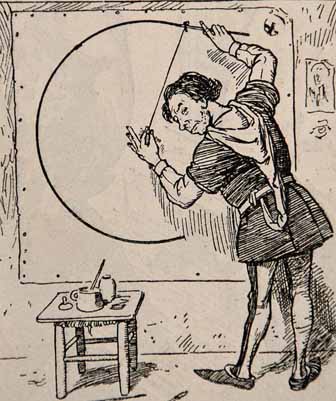

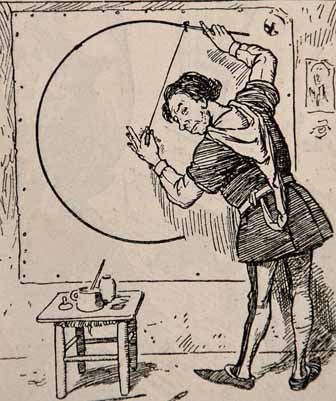

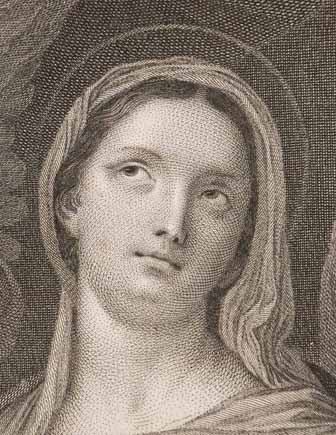

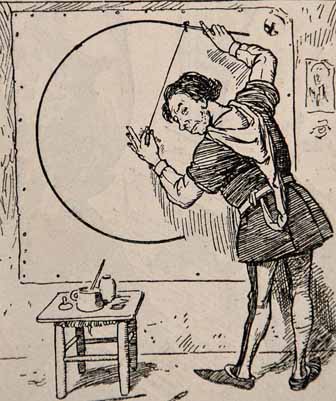

It is possible to view the history of art as a house with many levels. Fancifully, if we were to take a tour we might discover the prehistoric cave paintings at Altamira and Lascaux in the cellar before ascending to windowed rooms where we’ll find Egyptian art. Another staircase will take us to floors crammed with works from the Renaissance. As we climb further up the building we’ll pass through floors containing Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical art. The 19th century alone will contain numerous floors. By the time we reach the 20th century we’ll be many, many levels above the ground. Climbing on, we’ll reach the present day but we shouldn’t rest or pause too long. The tour won’t be over – this tour will never be over – for this is a house that will never be completed. Like all buildings, this arthouse has nooks and crevices hidden away that are rarely illuminated by the sun. In one of these nooks we might encounter paintings and drawings along similar lines to this: This charming work from our selection of drawings (appropriately titled Charmingly Finished; click here or on the drawing to see the full description) was sketched in 1823. The artist is unknown (it is initialled ‘W.T.C.’) but it provides a small insight into an overlooked subset of art history that first came to prominence in the 16th century. Known as singeries (from the French for ‘monkey tricks’), works depicting apes dressed as humans and acting in a human manner were first produced by Flemish artists; the idea was then taken up by painters and designers in France. Within in our house and its histories, the monkey has held numerous attributes. ‘Medieval and Renaissance man saw in the ape an image of his baser self. Thus it came to symbolize Lust, one of the seven deadly sins, idolatry and vice in general. In Christian art, with an apple in its mouth, it stood for the Fall of Man’ (Hall, 2001, p.10). A little further up the house, it was the artist who became most closely associated with the ape – both being known for their skill in imitation. This imitativeness was enshrined in the saying Ars simia Naturae – art is the ape of nature. In turn, this led to painters depicting ‘the artist as an ape, in the act of painting a portrait, generally of a female… This parody of man was extended to other human activities and apes were represented sitting at the meal table, playing cards or musical instruments, drinking, dancing and so on’ (Hall, 1989, p.22). The high point of anthropomorphised monkeys in art was during the Rococo period of the 18th century. Already a playful diversion in the arthouse, Rococo style was further enlivened by the introduction of monkeys in, for example, the work of Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), above. Although the vogue of Singeries largely died out in the nineteenth century, the monkey is still used (albeit without the anthropomorphism), for both parody and satire, in art today. Here on the top floor of the house we'll find monkeys in the work of Jeff Koons and far off in the distance we might find, beside a group of builders hastily constructing yet another staircase, something like this on the wall: And, as this is an imaginary house, we might find Banksy, spray can in hand, standing next to it.

References Hall, James (2001), Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art Hall, James (1989), Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art

You've left my

by the

Now is that

You've cleaned me out

you could say

Now is that

The

it gets

The more these

forget

That that is

You

you

Now is that, is that

A teasing

has

me out

Now is that, is that

The

it gets

The more my

frequent

Now that is

Beat me up with your

your walk out

Funny how you still find me

right here at

with a

and a

Now is that

that's making you

You've called my

I'm not so hot

Now is that

My assets

while yours have

Now is that, is that

It's the

That more or less survived

Now that is

Beat me up with your

your walk out

Funny how you still find me

right here at

with a

and a

Now is that

that's making you

You've made my

the

Now is that, is that

The

you

you

you cool down

The easier

is found

Now that is

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed